A few months back, I read an article by Jane Messineo Linquist for the IAABC about training puppies, Sit Does Not Mean Sit, which gave me palpitations and enormous food for thought. It’s a term she no doubt has been using for years. I was happy to come across it as it gave a name to a behaviour I’d been fostering in a number of my adult dog clients.

Definitely read her original before you go any further!

I apologise now to all my ‘normal’ readers… this will get geeky and it is a post meant for trainers and behaviourists, or even you great home schoolers who’ll see the practical applications for dogs under your care.

I also apologise that it took me so long to stumble on this term and technique but to be fair, I read a lot of dog stuff, and I haven’t heard anyone use this term or anyone talk about why the concept might just be the communications breakthrough for adult dogs with behavioural problems. I mean I had a major lightbulb moment. Seriously. It was, I am happy to say, something I was already doing, but reading more has very much crystallised my thinking. It’s reached a point where it’s good to share, even. I’m sure that like me, your dogs may also be using mands all the time.

The word ‘mand’ comes from BF Skinner, the father of behaviourism. He talked about it in many speeches and wrote about it in his book, Verbal Behavior. As you can tell from the title, it was a word he used for a verbal behaviour, so you’ll be forgiven for wondering what the hell it has to do with dogs. The linguistic skills of dogs? Surely not. I both apologise to Skinner for what I’m about to do with his word, and thank him too for giving me what has come to be a much fuller toolbox. He’d either hate the way I’m about to abuse it, or agree with it fully. Who knows? I’m going to explain more detail what I think the term mand means to me, and in the next post, how I use it with aggressive and fearful dogs.

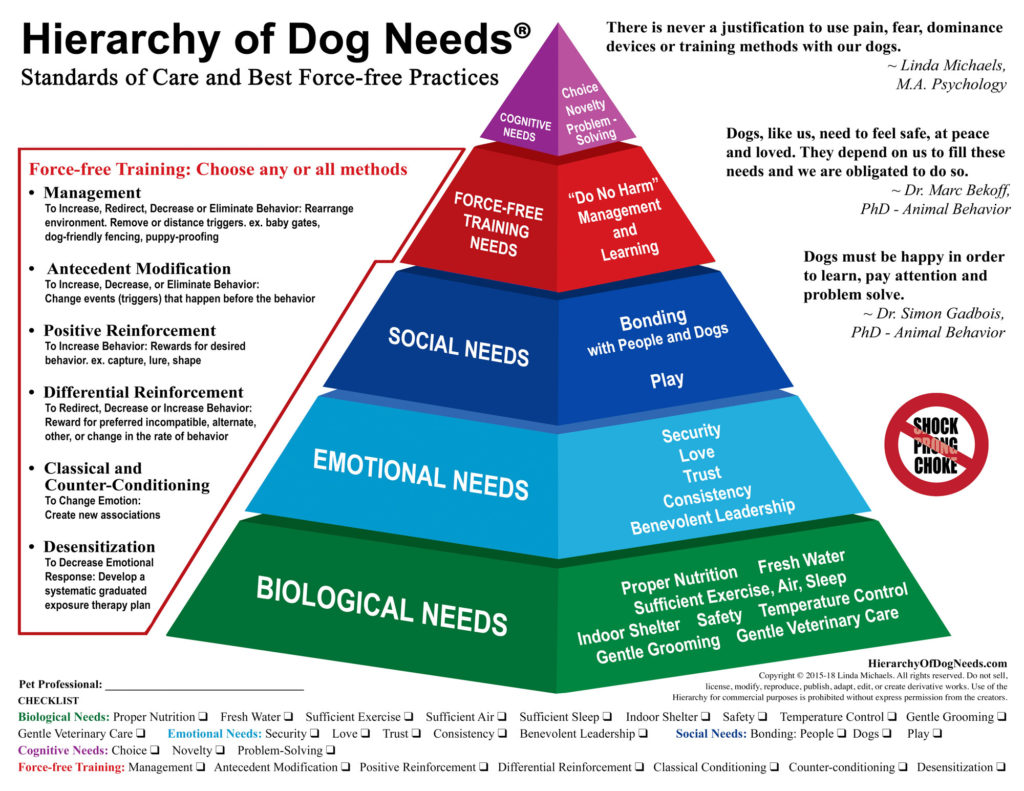

You’d also be forgiven for thinking Pavlov is our guiding father when it comes to behaviour problems, with a little help from Watson. Conditioned emotional responses. Counter conditioning. Gradual Desensitisation. In fact, there’s been such a backlash recently against ‘training’ for aggressive or fearful dogs that many behaviourists will be rolling their eyes that Skinner, oh he behind clicker training and both conscious and unconscious learning, could be mentioned in the same breath as aggression or fearfulness. We’ve been about the relationship, about the bond. About security and wellness. About being more relaxed and reading body language to help make decisions.

I still think that is a huge part of the process for many dogs. Most of it. I will say, though, that I have never found obedience or any other form of training to be mutually exclusive with building relationships. For me, those activities are as much about a partnership as dance or jiu-jitsu or capoeira or sailing a two-person yacht. The activity can be a way to build a relationship as much as anything else, but I definitely understand why people might say you can’t ‘train away’ fearfulness or aggression. Pavlov may well be on one shoulder, though, but Skinner is always on the other.

But what I’m about to discuss flies in the face of the ‘less training’ and ‘more relationship’ mantra that seems to be flavour of the month.

It also, and I want to get this clear right now, flies in the face of dominance-based training. Completely. It hands the reins back to your dog. In fact, think of it less as one of you being in charge of what happens and more like one of those dual brake pedal cars that instructors have, where you’re kind of letting the learner take over, just with some safety mechanisms. Mands let your dog make conscious choices about what happens.

So it’s about time I explained myself, and to do that I want to go back to the source. Skinner. Verbal Behavior 1957.

Skinner was writing about a type of communication that he called a mand. He used the term to mean verbal behaviour that is reinforced by a particular consequence or response. I don’t want to use the word ‘request’ because they are more than requests. It may also be a command or demand. It could be a summons. It can be information. It can compel you to do something. It could be a countermand. It may be mandatory, or it may not. You can see why Skinner liked it, as its Latin roots give us many words related to saying or doing something that compels a response in another. If you’re at all interested in British politics (because who isn’t!?!) you’ll have heard about mandates so often recently you’ll be familiar with the concept of giving power to someone to act on your behalf. Reprimands also… all things we do to influence the responses of others – or at least try to. So mands are more than requests. They can include commands or demands. Mand is the root that links them all. It’s a behaviour that says I want something or I’d like something or even that I insist on something, and that, in directing it at you, I feel you can help me.

But enough with the waffly theory. Let’s get practical. Let’s talk dog.

Dogs are one of the only species that mand with humans. They may not speak but they behave in purposeful and conscious ways to impact us or the things around them.

This is Heston. Most of Heston’s mands relate to play. A dropped toy at my foot is his mand to me to play. Not insistent. Not abusive. Not a command. Just a ‘Let’s play?’ His mands are delightful questions, offers, requests.

And if I reinforce it, those mands increase.

Let’s play, Monkey.

A mand can be an invitation, as this is.

Heston is not my champion mander, though. That was Tilly.

She became an expert at using me as a tool for her own ends. One of those lovely Dognition games was to put a treat in a sealed box and see how long it takes your dog to look at you for help. Heston didn’t look at me once. He just gave up. Tilly? 4 seconds.

Help, Monkey. My tupperware is stuck.

She was so good at it that if a sandwich fell down a well and needed rescuing, Lassie would be a second division Mander in comparison.

As you can see here, she’s quick off the mark to engage me as a tool to get exactly what she wants.

And another. You see also how Heston barks? Another mand. Barking is so peculiar to dogs (rather than other canids) and it is so much more frequent that I think sometimes we get lost in the fact that barking has a purpose. Unlike adult cats who do not meow at other cats, dogs do bark at other dogs, but barking definitely falls into that ‘human-directed communication’ that meowing does too. I suspect Heston’s bark here is just in recognition of the excitement Tilly has stirred up. He has no idea that she thinks there is something on the mantelpiece that she can’t get, and she needs my monkey assistance.

I don’t have videos of Tilly’s other mands, but she would also stick her foot in the water bowl and rattle it if she was out of water, and thump the door if she wanted to go out.

Tilly’s mands were very much about her physiological needs.

I mean, just imagine… a girl who came to me aged 5 with no house-training at all, and she learns how to tell me that she needs to go out! Mands are all about the dog teaching us to have their needs met.

Yes, you trainers may scoff as you may have done similarly, using bells or such like for dogs to say they want to go out. But that was you teaching your dog. Here, Tilly taught me. All I did was open the door and thus reinforce the behaviour.

With Heston, that mand to play was another one he taught me. Drop the ball or toy at the monkey’s feet and she’ll most likely give you a game.

For Amigo, that was so much more purposefully shaped by me. He had two behaviours to elicit contact from me. One was pawing me (always pretty hard) and one was resting his head on my knee. I consistently reinforced one with touch and not the other. He finished with a way to tell me that he’d like contact, please. But without leaving me with claw marks.

So it got me thinking… if dogs can mand for biological and social needs – indeed, we can even teach them to communicate their needs with us through operant conditioning and shaping – then why can’t we teach them to do so for their emotional needs too?

To be honest, I think that we have been. I think the industry as a whole has been moving towards helping dogs more effectively communicate their emotional needs in socially acceptable needs. The whole force-free husbandry movement with things like chin rests, consent tests, Bucket games and asking the dog a question (Chirag Patel) has been very much about teaching dogs to signal their desire to continue or not. I think mands are a part of this. We’ve been very much about consent and choice. We’re definitely getting better. But I think mands are going to help us bridge the final gap between what dogs want or need and ways to express that to us. A true partnership.

With mands, we step away from just passively watching dogs’ body language. Don’t get me wrong, I like watching dogs’ body language. It tells me a lot. BAT and Turid Rugaas’s calming signals have practically revolutionised my understanding of dogs non-verbal communication. Even their energy levels are so communicative.

The problems with watching this way and making choices for the dog are twofold as I see it. Firstly it’s very passive. It depends on us to have good skills to explore dogs’ unconscious behaviours. Secondly, it’s done TO the dog – we make the decision for the dog. By and large, I think we are better at reading dogs, especially as they get near to threshold, but the dog still depends on humans to make a choice for them without an active understanding of how that works. Also, it means dogs are perhaps left feeling uncomfortable until the moment they unconsciously make a signal like a lick lip to say they find a socially-mediated aversive stimuli unpleasant. Manding means the dog is actively communicating and making a choice – exactly what we love about the Bucket Game – in a conscious and deliberate way. They have all the power to tell us “Not today!”

How amazingly empowering must that be for an animal who has perhaps found themselves submitting to unpleasant stimuli because they had no choice? Just like dogs who have full bladders and no way to ask to go outside, dogs may have been feeling quite overcome by aversive emotional reactions to the environment without any way to say, unconsciously depending on an emotionally illiterate or temporarily unreceptive human to meet their needs. The way I see it is that once dogs begin to understand how to work the human world, it can’t but be hugely empowering.

Some dogs I work with have been so regularly ignored (often inadvertently) by their humans or have had to get by on their own initiative that it can be hard to learn to work with humans again. I feel sure from reading the notes from Tilly’s veterinary behaviourist before she came to me that nobody had ever asked Tilly what she needed or wanted. Her needs had been largely ignored for 5 years. Most of her most troubling behaviours, including guarding food and toys, stem from that sense of powerlessness, I feel quite sure. But Tilly learned. Or, rather, I learned to listen to what she was saying and in the end, she was a marvellously expressive little dog.

The same is true of Flika. She had had 14 years of fending for herself both physiologically and emotionally. Her ‘coping’ skills for separation anxiety are hugely destructive. This is a dog who fends for herself, who steals food items, who opens doors for herself and whose only mechanism for coping with loneliness was to bark and destroy. It’s quite sad that she never really asks for anything as experience has taught her there is no point.

So back to mands for dogs… really I just wanted to clarify what they are in this post, and follow up with how to teach them. I thought it was worthwhile outlining the principle and theory rather than the practice.

Whilst Skinner may have used the term ‘mand’ for verbal behaviour, it was quickly integrated into work with non-verbal humans. From teaching babies to sign and non-verbal children and adults to request, mands have a 40-year history of use in Applied Behaviour approaches that have helped humans communicate their physiological and emotional needs.

Where mands have been particularly effective is in the reduction of aggression, destruction and injurious behaviours. That was something the original article for the IABBC touched on, and something that gave me enormous food for thought.

Why it gave me food for thought was because I’d already been doing this as part of my rehabilitation programmes for the dogs with problematic behaviours and it gave a word to that practice. For the first time, it moved beyond instinct and into theory, with lots of practical guidance.

Unlike me, who’d stumbled on mands by accident, it should be a lot more clean – and my subsequent practice has been exactly that. It needs to start with a functional behavioural analysis (that’s a whole post in itself if you haven’t come across this) exploring the antecedents, motivating operations and consequences in order to consider the possible function or purpose of the behaviour. For most of my clients, that behaviour is very much about creating distance. But it’s not true of all dogs, for sure. One of the good things about a functional behavioural analysis is that it can certainly help you unpick the function behind behaviour that may appear uniform, like barking and biting, but also other things like compulsions or other ‘nuisance’ behaviours.

Once you have your functional behavioural analysis complete, you’ve identified the conditions in which it occurs and the consequences that keep the behaviour alive, you then need a behaviour from the same behavioural class – ie a different behaviour that serves the same function. You can see now why you need the analysis: if you don’t understand why the dog is barking or biting, then trying to replace it with a different behaviour that has the same purpose is impossible.

Dogs ‘mand’ all the time. Most dog owners will come to know instinctively what their dogs want, from Amigo ‘s very gentle reminder that it was dinner time to Tilly’s rather stylish bowl bashing to say, ‘Hey Monkey… Water!’. Some of us will be more used to those signals as we deliberately train them into service dogs for the blind and deaf, to signal in Search and Rescue work, to indicate presence of substances in scent detection, to work with us in many, many different environments. Whether dogs arrive at it through accidental shaping by owners or through purposeful operant teaching of a signal, the concept of manding is nothing ground-breaking.

But within the world of functional communication for socially unacceptable behaviours, that was an application that many of us were doing anyway, but that nobody had really put a name and theory to. That’s where I felt it broke new ground.

Within this milieu, mands are the dog communicating purposefully, consciously and intentionally with us to effect an environmental change.

There will no doubt be some backlash from those who think it is not a dog’s place to mand. In language, mands are commands (Go!) and subjunctives (Be still! I suggest that we go now) and interrogatives (Can we?) and optatives or wishes (Let’s…) and lots of other types of utterance. A dog’s behavior needn’t be seen as pushy if we think of it like this, and linguistically at least, it is collaborative and optional.

That for me is the cherry on the cake: mands build a relationship between those who issue them and those who help them meet their needs. It’s true collaboration (okay, for Tilly, I was just her extendable grabber, I know) but it builds trust. Because dogs learn through manding that they can operate us, and we have the ability to operate doors and can openers and things in tupperware, to make u-turns and to make scary stuff go away, the most

In the next post, some of the places where you can build mands with dogs so that they can make requests about their emotional needs. Then on to the how tos!