In dog rescue, particularly in what the French like to call the ‘Anglo Saxon’ world, there’s a mindset that I don’t often see in the French families who come to adopt our cats and dogs. I think it’s very specifically a dog thing, and you’ll see what I mean later, and very specifically an English-speaking phenomenon. I don’t know why that is, but I do know it gets in the way of our relationships with our dogs.

It’s about the dog in front of you.

This is Heston.

I know everything about Heston, after the day of his birth. I know where he was found. I know how many other puppies were found in a box with him. I know what his life was like up to six weeks of age and I know every single event that has happened to him in his seven years of life.

I know his DNA. I know which breeds got in there and what makes him 75% shepherd. I’ve got both Embark and Wisdom panels so I can fill in the bits I don’t know from his life before 1 day old when he was found in a box.

I know his medical history.

I know his best qualities and his worst.

So let’s take a ‘problem’ behaviour we’ve been working on since he was about 12 weeks old (and yes, I can tell you categorically when he had his first fear period involving humans and his first fear period involving other dogs). Heston can be a bit of a tit with joggers. We’ve largely mastered the sudden and unexpected appearance of Apex Predators on walks. We’ve mastered the sudden and unexpected appearance of Apex Predators mushroom-picking. We’ve mastered the sudden and unexpected appearance of Apex Predators on bicycles. We’ve mastered the sudden and unexpected appearance of Apex Predators and their packs of hunting dogs.

But joggers… Well they still bring out the worst in Heston.

Now, I can navel gaze as much as I like. I can look at the jigsaw that make up his pieces and say, well, groenendaels tend to be good at barking at threatening strangers (witness how easy it is to train their differently coloured Belgian brethren in protection sports) and I can say, well, he’s a dog and they can be protective of human resources, as well as territorial. I can say, well he’s a dog and predators don’t like bigger predators running at them. I can say, well, he’s a groenendael, and like many breeds or types of dog, he’s been bred to go in rather than hang back. If it comes to fight or flight, he’ll pick fight 100% of the time.

Or I could say, well, he maybe had fearful parents.

Perhaps it was a bad breeder.

Perhaps his mother had a third trimester stress experience that sensitised him to stress in utero.

Perhaps he was the first male in the womb and got a bigger dose of testosterone alongside that stress experience.

Perhaps he’s lacking in good maternal care. Maybe it’s because he was bottle fed.

Perhaps we should have kept the litter together.

He definitely needed better habituation to strangers. We live in a rural area and he didn’t see a jogger until he was way into his secondary fear period.

If I’d adopted as an older dog, perhaps I might have thought he’d been harmed by joggers. Perhaps he’s having flashbacks to some previous experience with people in lycra.

I’m being silly of course. I know this never happened.

But I can analyse Heston from his DNA up. All that’s missing is that early history. I can wonder if he’d be more accepting of large lycra-clad predators running at him had he been raised by a mother rather than a particularly spooky cocker spaniel.

I can pull apart Heston in a Philip Larkin fashion, wondering in what ways he was f%*ked up by his mum and dad, and which faults they passed on.

I can look into his eyes and wonder about inherited trauma.

I get a lot of this kind of questioning from the Anglo Saxon owners who approach me for behavioural work. Why are they like this? What’s going on? What caused it? As if by understanding cause, you can change behaviour.

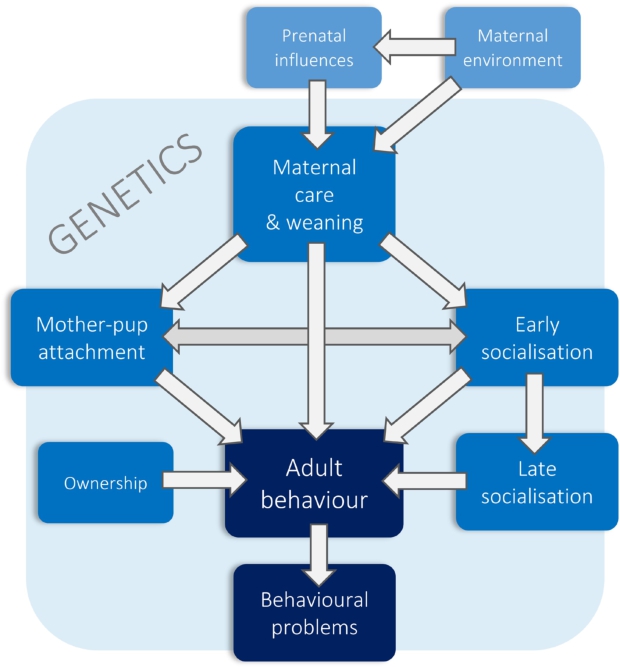

I show them this:

This ‘soup’ is what makes up a dog (and more than this, believe me).

We hear often ‘no dog is a blank slate’ as if genetics are the be-all and end-all of behaviour. And we hear too trainers who claim they can change all behaviour as if genes and history don’t matter.

The truth, as always, is somewhere in the middle.

It all matters.

And, as I said, more too.

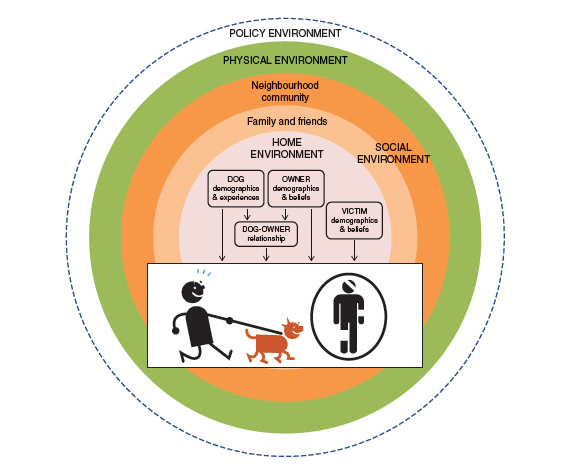

This diagram kind of picks up where the other left off… it’s what contributes to a dog bite. But it’s actually what contributes to ALL behaviour. That social environment is crucial. It all matters. Heston is a rural dog in a land where joggers don’t understand not to run at dogs. He doesn’t see joggers. He doesn’t know joggers. I have to drive 30 minutes to even see joggers in any predictable way.

Your dog will be influenced by these things too for their behaviour.

So when people ask me why their dog is ‘like this’, my answer is this:

“You can know every single piece of the puzzle and it still won’t change behaviour.”

The truth is that we Anglo Saxons torment ourselves with the whys and wherefores. That’s especially true when we have a rescue. We make up stories to fill in the gaps… they came from combat rings, they were abused, they’re street dogs, they were neglected, they had a traumatic second fear period…. ad infinitum.

This poses a challenge for two reasons. The first is that, as I said, it doesn’t change behaviour. It doesn’t actually help you understand the behaviour of the dog in front of you. It’s frustrating and without cease. The problem is that when you start unpicking causes, you start apportioning blame. If only he’d had a better socialisation period. If only those knobs didn’t leave him in a box. If only I’d not taken him to that market that time. If only….

In therapy, this is known as the ‘tyranny of the shoulds’. Karen Horney said in her writing that these prevented us from moving on. They weighed us down, gave us unreal standards to live up to and prevent us from change. Shoulda Coulda Woulda.

The second reason, apart from the frustration of never being able to put that spilt milk back in the bottle or lock the stable before the horse bolts, is that it gives us built-in excuses.

‘Oh he’s like that as he had a traumatic event during his primary fear period’.

It’s an answer.

But it’s a reason too. An excuse. A statement that says ‘I’m sorry: the milk was spilt and it wasn’t my fault. Please excuse my dog who is behaving like a bit of a tit.’

Both of those things prevent us from moving on. They prevent us enjoying the dog we have, taking stock of how wonderful they are and saying, ‘do you know what – let’s sort out this problem behaviour’ no matter its genesis.

Heston very much enjoyed sniffing in bushes last time we experienced the sudden and unexpected appearance of Apex Predators jogging in too-tight fluorescent lycra. We play ‘find it!’ when joggers come by, and strangely, this game avoids the need to behave, well, like a dog.

I’m going to take away my pride at my work and my canine ‘offspring’ and his ‘journey’. It’s a simple recipe of gradual desensitisation paired with food reinforcers (Pavlov) that turned environmental threats into a cue that a game would begin (Skinner). All pretty good practices endorsed by the best clinical animal behaviourists.

I’ve never known this recipe fail to modify behaviour when done properly under supervision of someone who knows what they’re doing.

So, instead of passive acceptance and instead of naval gazing, I now have a dog who feels like joggers are just random cues in the environment that treats will suddenly rain from the sky. A dog who looks forwards to the presence of joggers when he is in my company because, well, that’s nothing for us to be bothered about.

It’s about looking at the dog you have in front of you – one exhibiting a problem behaviour at least – and asking, ‘what can I do to make the world feel safer for you?

Sometimes, I admit this is not always possible to a complete degree. I can’t make Flika feel completely safe in storms. She’s had 14 years of working it out for herself, I would guess. But I can shut the shutters, stick on some Bob Marley and read her a book. Last storm, she only tried to eat the door once. Small progress counts. That’s better than trying to eat the doors without stopping for 30 minutes.

Instead of wondering if she has PTSD about times she was shut in a warehouse or left outside on patrol during a storm, I move away from deep causes. Identify triggers, change behaviours.

The truth is that we Anglo Saxons enjoy a bit of navel gazing and puzzle solving. I’m not suggesting you ignore your dog’s history and never try to make sure you understand all the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle. What I am saying is that we need to stop this holding us back from working on behaviour problems that show our dog feels uncomfortable with the world, and we need to stop excusing it.

Those excuses mean that we allow our dogs to continue behaviours that feel unpleasant but necessary to them.

It stops us finding solutions.

And also, we don’t do this with cats. We do this with dogs because they occupy a unique niche in our world as quasi-humans. We want to understand all the components as if they were human. We don’t do this with other species.

‘Oh that elephant is just acting out because it had a traumatic single learning event in their secondary fear period.’

‘My rescue cat was obviously abused by lycra-clad joggers.’

‘That beaver’s mother must have had a traumatic third trimester.’

There’s a lot of talk at the moment about whether animals have memories, whether they can conceptualise the future and whether they live in the moment. More so than ever with dogs. You know, quasi-humans in their ‘special’ relationship with us.

Look to your dogs. They will tell you. You don’t need science to prove this stuff. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Watch your dogs. Tilly found a big bone once in a field. She couldn’t carry it back as it was too big. Over 3 months, on each walk in that area she would progressively move it closer to the house and rebury it for safekeeping. 100m every few days. If that’s not both memory and planning, I don’t know what is. But sure, dogs live more in the moment – and so should we. Live in the now, look at the dog in front of you right now and instead of vivisecting behavioural causes to the nth degree, look to how you can move forward. Especially when you don’t have all the pieces.

Say, ‘Oh well!’ to that history. Tant pis.

Solutions, not excuses and ballast that stops you progressing.

Think ‘Gonna’, not ‘Shoulda, Woulda, Coulda’

You will never put spilt milk back in a bottle, but if you keep spilling it, you need to ask yourself how you can change so that in future, less is spilt, or none at all. When our horses bolt, it makes no sense to lock the stable behind them. But it’s a good reminder to lock the stable door before they run off next time.

Look at the dog in front of you right now, not the pieces of their history, and know that you will never understand everything. Even if you do.

Let’s stop psychoanalysing our dogs, vivisecting every aspect of their behaviour, looking to explain it all with deep-seated biological, neurological or historical reasons that can’t be changed. Say ‘Oh well!’ and work on what would make the world better so those behaviours would be surplus to requirement. Let’s stop talking about ‘traumatised’ dogs and live more in the moment with them, helping them to cope with the future. After all, we’re all heading there, dogs included. The past and the future, time’s dual arrows, are predicaments of human beings, not animals.

Next time, I’ll be writing about building resilience in dogs to help them for that future.