Hands up if you’ve got a dog who’d run to the ends of the earth chasing a car? My hand is well and truly raised, isn’t it Miss Flika? Let me tell you, it’s not such an easy task to try to retrain a 14 year old girl who goes nuts at the sight of a van, lorry or car.

Let’s face it: for most dogs, up until the 20th century, life was not filled with mindless machinery. Horses were as likely to give you a kick to the head if you got a bit frisky with them. Carts didn’t go as fast, they weren’t as dangerous and they didn’t make all that noise and machine smell. Chances were there was a man attached to that cart who would have given you strong incentives not to chase. But kicking and whipping dogs are no solution.

Life was easier for dogs before we invented automated machinery and things that moved.

In such a world, it wouldn’t even matter if your dogs did chase things most of the time. I’d have little problem with my dogs buggering off if there weren’t cars about. I could probably even live without as much fencing. It’s the things that we’ve invented for dogs to chase that are the very reasons we don’t want them to chase: they’re dangerous.

The problem with our dogs getting off the property and chasing is that so many dogs – as with all kinds of wildlife – end up victims to the machines we’ve brought into their lives.

It’s fairly easy to say what is behind such behaviour, even if we don’t have a solution for it. Some of our very earliest work on canine vision back in the 1930s showed that dogs, like humans, more easily detect a moving object than a static one.

A study of police dogs in 1936 determined that they could see moving things almost a kilometre away. The same static things didn’t cause a speck of interest until they were less than 500m away.

That makes sense for a plains predator: whilst vision may not be a dog’s primary sense, being able to detect a fleeing animal is a helpful life skill. It’s also why Heston doesn’t see hares ‘frozen’ (even if he can smell them) and why as soon as they decide to flee, that’s when he decides to move.

Not only that, for long-nosed breeds, from sighthounds to German shepherds, daxies, poodles to collies, the placement of the eyes on the head give them superb binocular vision. That makes them exceptionally good at scanning the horizon for movement. They have wide-angle vision.

It gets worse: those long-nosed breeds often have a concentration of the sensory cells that capture light and shadow concentrated in a long horizontal visual streak whereas other breeds tend to have a much less pronounced visual streak. Better eyes to see things moving horizontally across that already enhanced binocular field of vision.

Add in long legs and what you essentially have is a dog designed not only for chasing (see you later, daxies!) but a better perspective.

Stick in a bit of desire to control moving prey species that we’ve bred for with mainland European shepherds and other herding dogs, and you have the perfect biological recipe for a dog that likes chasing stuff to speed it up and slow it down. That’s enhanced every single time they do it with a nice shot of dopamine to help them feel good, reinforcing your dog every time they do it and making them crave doing it when they’re unable.

The simple motion at speed of something in the distance sets off a set of age-old predatory pre-programmed behaviours that have clicked into ‘play’ mode long before the visual cortex says ‘hold on a second, I don’t think it’s an elk.’ A twinkle of light, a sudden shadow moving in the distance and boom – Chase Mode Engaged.

It’s not a surprise to find a lot of dogs who engage in these behaviours are herding dogs. Effel chased bikes, cars and lawnmowers in his misguided attempts to faire la rive like good beauceron are supposed to do when a distant sheep gets a jiggle on. His genes are saying ‘Keep The Moving Things from Moving, Effel!’ and I’m saying ‘Effel, get away from the flipping lawnmower, you idiot.’

It’s not a surprise that Miss Flika feels the need to go and tell that car that he has no right whatsoever to be causing flashes of light in the distance.

And it’s not a surprise that collies, GSDs and malis, when kept on a lead, will be so frustrated with the sodding, uncontrollable moving things that they will bark at it like a frustrated sergeant major watching his corporals run willy-nilly through a battlefield without a single sense of cohesion.

For other dogs, it can certainly be a clear sense of fear. Moving machinery that seems to work on its own would be utterly incomprehensible if you weren’t used to it. Most of that is to do with a lack of habituation: most streeties, for instance, that grow up in towns, are used to the comings and goings of traffic. I was watching – with a certain sense of mirth – a dog trainer with a shepherd working on habituation to traffic. What made me laugh were the large number of streeties his videographer also captured who were just ‘meh, cars’ wandering in and out of doorways as they went past. But deprive a dog of those activities to see traffic regularly from a young age, and you’ll almost certainly have a dog who is fearful around traffic. That can be hard to see as different from dogs who chase cars, since predatory behaviours and aggression can look so alike. Certainly, I’ve worked with dogs whose main aim was to stop the scary, smelly thing from moving and the arrival of any car or motor noise was met with ambivalence and over-arousal but it looked like common-or-garden chasing behaviour.

Lack of vital learning is often a core factor whether the emotional roots of the behaviour are fear or chasing. Heston is sensible around cars, unfussed about machinery and not interested in the slightest by cars, bikes or skateboards going by him at any speed or distance – but then we live on a main road. He’s been used to cars and our local Tour de France types since he was 6 weeks old. The only cars that annoy him are ones that slow down outside our house, because cars don’t do that very often and who knows what crafty thieving and attacking they’d get up to if he didn’t tell them to bugger off. That’s much more about territorial behaviour. I could guarantee that he wouldn’t chase a car 100%.

Whether it’s a fear response or a chase response, you’re probably best working with someone who can help you determine the motivation behind the behaviour. Not that there’s very much difference in how you’d go about working with a dog who is chasing through fear or excitement, but on the one hand you are counter-conditioning as your dog is afraid, and on the other you are desensitising because your dog is over-excited and the predatory ‘play’ button is activating before the visual cortex is saying “it’s a car” and the rest of the cortex is saying “we don’t chase those”.

If your dog is fearful, you absolutely don’t want to use punishers or restriction. I picked up a client recently with a malinois who’d been car chasing and the previous trainer had ‘reminded’ or ‘interrupted’ (their exact words) the dog ‘with their foot’ (their words) not to chase cars by walking less than a metre away from cars going 40mph or more and ‘reminding/interrupting the dog with their foot’ if the dog started to panic. I’d not have said ‘reminding/interrupting with a foot’, I’d have said kicking the dog up the backside. Words are not meaningless and if you feel you’re being given euphemistic advice that involves physical contact with your dog, chokes, chains or shocks, then you need to find a better trainer.

The problem with such punishers is that the dog comes to associate moving objects with YOU giving it a kick up the backside. You’re part of the common denominator. And anyway, what does the dog do when you’re not there? They still chase. Punishments only suppress behaviours when you’re present: they do not teach the dog what to do.

Plus, you’ve got to punish them for every single element you want them not to chase rather than teaching them one single action to do in all cases. You may very well have spent all your time ‘reminding’ your dog and ‘interrupting their focus’ with cars at 10m, but what happens when they see one at 400m? Punishments can seem quick and they’re offered as simple remedies, but the reality is that they suppress behaviours lulling you into a false sense of security that the behaviour is dealt with, so that you let them off the lead only for them to chase the first moving thing they see. Punishments also rely on you being near the dog – and that’s counter-intuitive for recall. If you punish a dog around moving things, the first thing they’ll want to do off-lead is get the hell away from you. Say bye-bye to your recall.

Also, if that ‘nudge’ or ‘reminder’ stays a gentle prod, sooner or later your dog will ignore it. Then you’re faced with a choice to escalate because your dog has got used to your pokes and rib touches. So then you’re into the realms of heavy artillery punishers – chokes, prongs, shocks. If you’re here and you think these are acceptable things to use on a dog, then you’re probably going to need to read on.

These tools lull you into a false sense of security. We reason ourselves into ‘it’s for their own good’, ‘it’ll save their lives.’ Well, chase instincts are so much more basic and fundamental that fear of you zapping them with a taser probably won’t be enough eventually.

So please don’t punish your chaser or (especially!) your fearful dog if they are reacting around moving targets.

So what ARE you supposed to do?

As with everything in dog training, there are no quick fixes.

What we need to work on is habituating the dog to moving objects. That means desensitising them to moving targets at a distance, or counter-conditioning fearfulness. We need to activate learning that means your dog sees a moving target and they know how to handle it. Instead of having a sensitive ‘chase’ button, the neural pathways that help them sift out the wheat from the chaff become more adept at sorting ‘chase’ things from ‘not chase’ things. That’s much easier with mechanical objects because there’s really only one aspect of them that’s worth chasing – the movement – and once there’s been a bit of thinking, that’s easier than if you’re working with hare or deer and the likes. Dogs don’t bite static cars. Effel ignored the lawnmower 100% of the time when it was still. Well, he peed on the wheels, but that doesn’t count. What we’re teaching is ‘you see that thing in the distance? Give your brain time to process…. go on…. go on…. you got it! It’s NOT a wildebeest! Well done!’ I have never (yet!) worked with a dog who chased static cars. Interested in them, yes, but if your dog is racing up to parked engine-off cars from 100m away, you’ve got an anomaly for sure. It’s the movement that’s everything for a chaser. On the other hand, if the engine-on parked car is creating a reaction, you’ve either got a learned response that the engine on means the car will move soon – hoorah, good signal of a game of chase! – or you’ve got a dog who is afraid of the noise. Effel became very interested in the lawnmower when it was idling because it meant more than likely, a very good game of ‘being a beauceron’ was going to follow. So do a little thinking about how your dog behaves around ‘dead’ machinery, ‘noisy non-moving machinery’, ‘slow rolling machinery’ and ‘fast machinery’ – it’s all part of the picture.

For chase behaviours, the desensitisation is going to start REALLY far away. Do you remember I said the police dogs could see a moving target 900 metres away? We may need to start there!

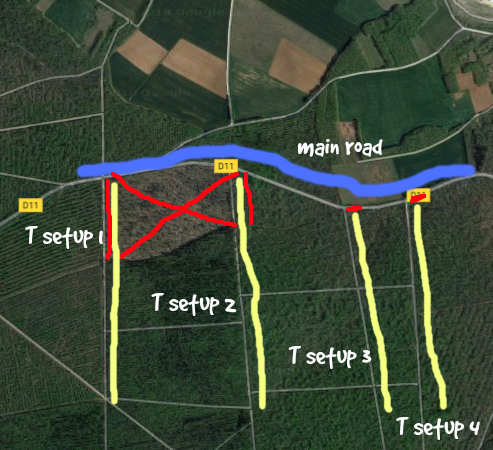

What you need is a set up. A set up is an environment where you can control most of the factors. A good set up will mean easy, clinical progress. The fewer complications, the more ‘scientific’ and clean it becomes. For me with moving machines, that’s a T set up (see image below). The long bit of the T may need to be up to a kilometre long with a direct view – at the dog’s height – to the cars. The top of the T is a main road. I like the long bit of the T to have trees or buildings or something to mean that the cars are only going to pass into view for a very short second. Visual chasers are not usually that bothered by the sounds of traffic, but for a fearful dog or a dog who has practised chasing cars, I may even need to work on sound or smell alone. Basically, if I get into the field and the dog is way over-stimulated by traffic when we’re more than 500m away, I need to back it up and it’s probably sound that is setting them off rather than sight.

The yellow path is 1.2km long and if there are issues, I can always go to the other side of the slower road for a 1km path in a similar set-up and zero distractions. However, it’s harder to get to and there isn’t so much traffic on it which means I can wait hours for a single car.

On the dark blue road, there is lots of traffic at a fairly constant 80 or 90km. There are no other distractions – few other people on this section of track and as long as I check it out before, I can park far up it and start 600m away from the car. The traffic on the blue road is intermittent as well, and that’s REALLY important for what will happen next. What you don’t want is a steady stream of constant traffic with no gap between. There have to be gaps in the traffic for the connection to form with the dog.

Just as a side note, if you’re working with a noise-sensitive dog, pick a day without a temperature inversion or rain… those days make sounds much louder and can be a challenge.

So we start 600m away and start walking towards the dark blue road. I stop every 20m or so, allow lots of sniffing and interaction, but no toys and no food. Toys amp up the adrenaline and I need a calm ‘thinking’ dog not a ball maniac. The food can ONLY be associated with the traffic so I’m saving that for later.

I want to get to the perfect point where the dog is noticing the traffic but not pulling towards it, but I absolutely don’t want to do it without my secret weapon, so I’m going to listen for cars, watch for a reaction and wait until I’m getting to the ‘threshold’ point where the dog is likely to notice the next car along. As soon as they see it, I’m going to pull out my magic weapon: the very best food they’ve ever had… something disgusting and smelly and rich and full of dog yummies. And as soon as the car is gone, the food is gone.

The reason I go with something surprisingly tasty and amazing is because the more surprising the experience, the more we learn from it. The more we remember it. Think of all the nights out you’ve had, the restaurants you’ve been to, the sports matches you’ve watched… which ones stick with you? The ones that were surprising. Being surprising helps associations and memories form much more quickly.

After, the food goes away and we stay at the same distance. I like a short interval between the next car, but it has to be the very next car, and the food comes out again. Food-food-food until the car is gone, and then the food goes away. Car appears in view = food, car disappears = food stops.

I need to confess that dogs are SO quick at getting this. Two times with one collie. Three with the mali. The next car comes and I’ll hesitate the briefest of moments – I want that look back, that ‘where’s the food then?’. If the dog isn’t quite getting it, I won’t hesitate at all, just keep car-food-food-food-car gone-stop. It might be that this might happen twenty times and they don’t get the connection. If you’ve set it up properly though and the thinking brain is on rather than the chase mode, you’ll find they get it really quickly.

The moment the dog looks to the car and looks back to you, you have won a major, major victory. It has clicked.

All those lab-rat behaviourists said it should take 5-7 times of those surprising phenomena for an association to form. I’m with them on that.

And once I’ve done a few trials, that’s it, game over. We go home. Always finish on a win.

Next time, I start at the same distance, maybe even just a little further back, and a different set-up zone. I don’t want the dog to be thinking ‘right, we’re here, that means sausages’. I want them to think ‘Huh! That works here AS WELL?! COOOL!’

As you can see above, the choice of set-up situation is really important. Here, I’ve got 4 possibilities. Set-up one and two have long, straight, quiet paths that give an eye-line to a road about 500m away. However, between the two there is a part of the wood that has been coppiced, and it means the dogs can see cars moving for about 10-15 seconds. They are okay for later in the programme – in fact, they’d be great for when I need to increase distance because I’m increasing the duration the dog is exposed to the moving car – but they are not good for my second experience. Set-up 3 involves a T that is on a part of the road with a bend and a steep hill, so cars are going 40-50kpm there – that slows them down and increases the time the dog is exposed to the moving vehicles – neither are good for a second experience either. Set-up 4 is perfect. Cars are speeding up again, short period of contact, long straight road and the trees either side of the pathway that help create a really short period the car is present for. The path gives a clear sight-line for the dog (and remember to check out the sight-line from your dog’s height, not yours! YOU might be able to see moving vehicles with your increased height of 1m70, but your dog, at 70cm will have a much reduced field of vision and even small inclines can completely obscure the dog’s sightline.

Check out the set-ups before you take your dog. No use doing them if the path is heavily-travelled or busy, or filled with other things your dog finds overwhelming like lots of scents. Working with a behaviourist who has done programmes like this before will mean they should have good local knowledge of where will work. I’ve got a bank of 50 or so good locations (including one with a sightline of 2000m to a burst of fast road with intermittent traffic that is the absolute dream set-up for dogs like this – former rifle range!) as the better your set up, the more chance of success.

I give them a couple of days of no-chase car-free days between training and so every single car they’ve seen is met with yummy, yummy goodness.

At this point, I also start to add another behaviour – a thing I’ve taught them to do that I want them to do when they see a car. For most dogs, I teach a hand touch or a shoulder target where they touch your hand with their nose or their shoulder to your knee. This time, when the first car goes past, I’ll do a free food session – just to show this is still the same here. And when the second goes by, I’ll ask for the behaviour – one I know they have really, really solidly. Sometimes that’s a sit, but there’s no reason it has to be anything particular. I like hand touch because it disrupts their looking at the car and I can also add duration later and get a 2-second or a 20-second nose-to-hand. That is one calm dog who is thinking, not a mad dog chasing a car. But Flika likes the ‘shepherd lean’ (you know that thing they do where they lean on your legs) so we went with that. She comes back to me when a car comes and leans on me. I also like this because I’ve been able to swap some food for cuddles – but not every dog appreciates that. Will Work For Petting is very dependent on you dog. And Flika still appreciates the sausage-petting combo SO much more than petting alone.

After that second session, we practise over the next few weeks at shorter and shorter distances, never ever letting the dog go into manic chase mode. If they feel over-excited and edgy, I’ll skip cars on that day and do a car-free walk instead. I also build in lots of non-training days. You’ll be surprised by how quickly your dog will pick up on the ‘no chase’ thing, but be prepared for it to take up to 6 months. That way, you won’t be disappointed.

I also write down SMART targets starting with the end point at a 6 month date. I think of where we are now and where I want to be. And then I work out where I need to be at 3 months, 6 weeks, 3 weeks and 10 days from my starting point. Imagine I’ve got a dog who is reacting to cars at 100m, but unreactive/noticing at 150m. This would be my rough plan.

In 6 months’ time, the dog will walk without reaction alongside fast moving traffic

That means in 3 months’ time, the dog will wait without reaction as fast-moving traffic goes past

That means in 6 weeks’ time, the dog will wait without reaction as fast-moving traffic goes past 20m away.

That means in 3 weeks’ time, the dog will wait without reaction as fast-moving traffic goes past 50m away.

That means in 10 days’ time, the dog will wait without reaction as fast-moving traffic goes past 100m away.

Small, measurable, achievable, realistic targets that I can adapt if I need to. I’ve not got a rat in a maze pressing a button for food, I’ve got a dog in real life with a biological button releasing good shots of dopamine for chase behaviours.

That said, when I’ve broken it down like this and I’m regularly practising, I’ve never found myself getting to 6 months. But I go at the pace the dog dictates.

This kind of learning moves from the Pavlovian association of cars = food to cars = hand touch = food then to cars = hand touch = occasional food. This may be where you’ll need a trainer to explain intermittent vs fixed rate reinforcement schedules and it all gets arse-numbingly boringly science-geeky.

The main things to remember are:

- we’re working to put some ‘thinking’ steps in between a visual trigger and chase behaviours

- we’re working to break habits, and if your dog has been practising them for X amount of years, be prepared to put the same amount of time in to teach them to stop

- most people understand how to form associations but they are far too close and work far too quickly

- most people are miserable when it comes to payouts – this is worth more than dog biscuits

- this can work with ‘real’ prey but your dog’s visual cortex is pretty likely, instead of going ‘ignore that machine’ to say ‘that’s a hare, dude, go get it!’ so working with livestock (and people) can be a little different and is dependent on their emotion, the context and their motivation

Partly the success of this method – whether for chasing or for fearfulness – relies on gentle, gradual, planned habituation to moving machines. I’ve used cars as an example, but I’d use the same processes for bicycles and scooters or lawnmowers. Start far enough away that the moving object is noticed but not that near your dog is straining towards it. Your dog will partly be learning just by repeated exposure, over and over again, to things they want to chase – just at a mild enough level that they get used to it. For Effel with the lawnmower, that involved me being off the mower and letting someone else ride it. We started much closer than I would have liked to as my garden is not that huge, but it took a bit of work for him to be around the mower simply because it had been so enjoyable when he did it the first time.

Another part of the success of this relies on pure science stuff where a trainer who has a lot of practical experience with conditioning will be a real asset. If you’re not exactly sure on how to set up a counter-conditioning programme or a gradual desensitisation programme, get in touch with a local behaviourist and ask them to help you out.