“It’s simple, really…” I found myself saying. “Your dog has a small sink. She overflows easily and doesn’t drain well…”

It made sense to me at the time, but it sounds like awful nonsense without a justification.

The sink metaphor is one I use frequently though with owner to explain why their dog isn’t coping with life.

You might very well be wondering what sinks have to do with stress and why some of our dogs don’t cope with the life they lead, or why they ‘suddenly’ seem to find life so hard.

Why are some dogs ‘bomb proof’ and some dogs on a hair trigger?

Why does it take some dogs seconds to recover from things, and other dogs seem to take days?

Why do some dogs seem to tip over more easily into fearfulness or aggression, and why isn’t it a good idea to flood your dog?

Your sink is your body. The taps are the centres of your body that control the release of hormones, neurotransmitters and other bodily chemicals. I imagine them like water – adrenaline, cortisol – all those fancy biological bits that our brain turns on or off, that pour into our bodies and make us ready to fight, to freeze or to run away. There are certainly more taps running into our sinks than adrenaline or cortisol, but these are our ‘stress’ chemicals, that help our body deal with life.

Lots of factors decide how much pours out of those taps and how well your sink is able to handle the flow. You might, for instance, have a ‘normal’ flow of adrenaline and cortisol and your sink may just not be able to drain them quickly or efficiently. It might be too small, overflowing at the smallest fright. Tilly is a bit like that. It doesn’t take much for her to ‘flood’ – and the puddles that go with that are a much more literal vision of a ‘sink’ that floods too easily. Tilly doesn’t cope well with stress. When her sink floods due to a stressful event, she alarm barks and she pees.

You might have a fairly big sink that drains well – coping with life admirably. But what happens when your ‘taps’ release more of those chemicals than usual? You might also overflow too. One reason a body will do this is if you’re subjected to something acutely stressful. Chronic stress can do this as well – when it just accumulates and accumulates. Dogs also get illnesses such as Cushing’s – there are many reasons they may get Cushing’s. But Cushing’s tells the body to produce lots and lots of cortisol, like leaving the tap running at full flow all the time. Steroids can also have the same effect. Addison’s disease is the flip side of that coin, where not enough cortisol and adrenaline are released.

What largely dictates the size of your sink, how well you are able to cope with the flow of cortisol and adrenaline, is dependent on a number of things.

Genes are one. Bombproof parents are more likely to have bombproof babies. Breed is also a factor for dogs: it is without doubt that some dogs are more nervy and less able to cope with stressful situations or change than others.

A lot of that determines how big a sink you’re going to be born with.

Then socialisation (between 3-12 weeks and then continued more gradually up to adulthood) also influences the size of your sink and how well you cope with stress. Sadly, we know very well the risks of not socialising dogs and not inoculating them against stress… you can take a dog born with great parents and from a rock-steady breed, and if you don’t expose your dog to the world they’ll need to live in, you’ll end up with a dog whose sink size shrinks.

Sometimes, that’s just a little bit.

Heston, my shepherd, came to me aged 6 weeks. We had lots of exposure to cars and the outdoor world, not enough to people, vets, groomers and dogs, and none to stairs.

You’re wondering why I said stairs.

Didn’t cross my tiny mind that his fairly usual-sized sink might not be able to cope with stairs. Full-on fear overload because I forgot I might not live in a bungalow or have bungalow-dwelling friends all my life. Think of me carrying my 30kg dog down a spiral marble staircase as he literally pisses himself… and you’ll realise why I forgot to make his sink big enough to cope with stairs and why that posed a problem.

Habituation (getting used to things in life), desensitisation (getting used to the scary stuff gradually) and socialisation (knowing how to interact with people, dogs and other animals) are crucial influencers on the size of sink your dog ends up with.

A dog born with a fairly small sink may, for instance, expand their sink through a careful, planned, gentle programme of habituation, desensitisation and socialisation.

You have got a very brief period of time with a puppy to make the most impact – from 3 weeks of age to around 12 weeks. After this, your job is much tougher.

However, a lot of people do the early stuff (and get it wrong by accidentally overwhelming their young puppy) and forget to keep doing it – a lot of the good work you can do early on can be diminished by stopping at 13 weeks and not keeping it up at a gentle rate. But if you only start at 13 weeks – illness and vaccinations are two common reasons this step might get overlooked, but lack of understanding in puppy rearing is also a big factor too – then you are facing an uphill battle.

As we age, the size of that sink gets much harder to change. It’s much more fixed.

That’s not to say I can’t grow it gradually (I didn’t just give up to carrying Heston upstairs or accept that Tilly would pee every time anyone came to the house) but it’s a task-by-task scenario that can take weeks or months. I can’t turn that tiny hand sink into an enormous Belfast kitchen sink once that socialisation period is closed.

And that’s also not to say it can’t shrink overnight. A one-off traumatic experience can be enough to change your dog’s catering sink into a hand-basin. Those kind of events are rare though. Let’s make that clear.

So a small-sink dog might be a poorly-bred puppy-farm-raised nervous nellie of a -doodle whose owners followed vet advice to the letter and never took the dog anywhere until it was 16 weeks.

It might be a dog who started out with a great big sink, but who was over-exposed constantly to stressful situations and lived in chronic stress.

It might be a dog in pain or ill-health, suffering from acute stress.

And your big sink dog, well, we don’t put enough into making dogs with big sinks in my opinion. That takes a lot.

Rock-solid temperaments in parents, great genes, careful breeding programmes, thoughtful socialisation up to 12 weeks and beyond…

Genetics, breed and parentage fix a lot of the size of a sink. Not all, but a fair whack. Socialisation from 3 – 12 weeks fixes a lot of the rest.

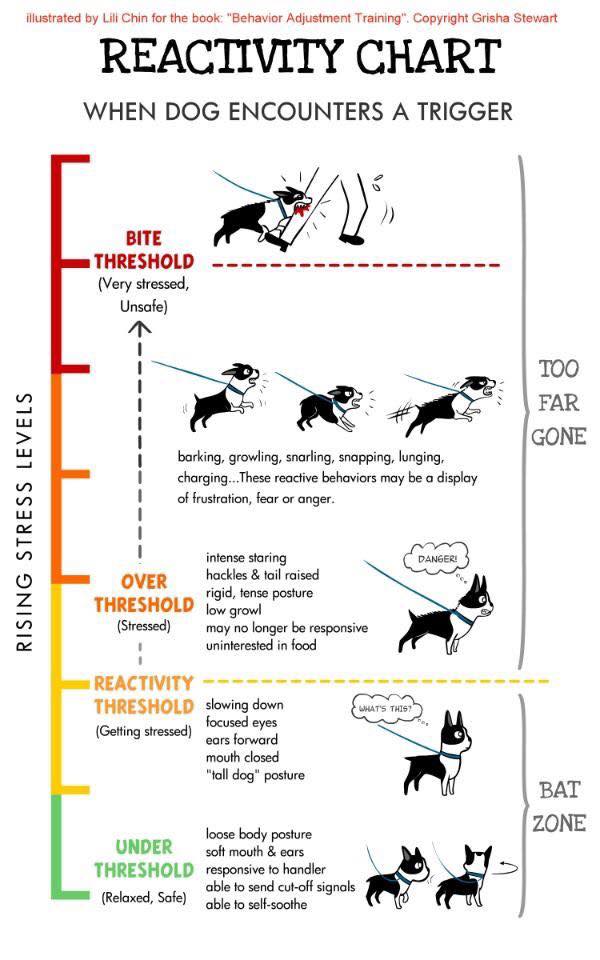

What happens when that sink floods is what worries us most about dog behaviour. Aggression. Fearfulness. Running away. When our sinks flood, we’re in dis-stress. And stress affects so much more than just causing Tilly to pee when guests arrive.

Stress makes it easier to learn a fear association and turn it into a long-term memory. A flooded sink makes us hypersensitive to the environment and to remember it. It’s why we have flashbacks and develop phobias.

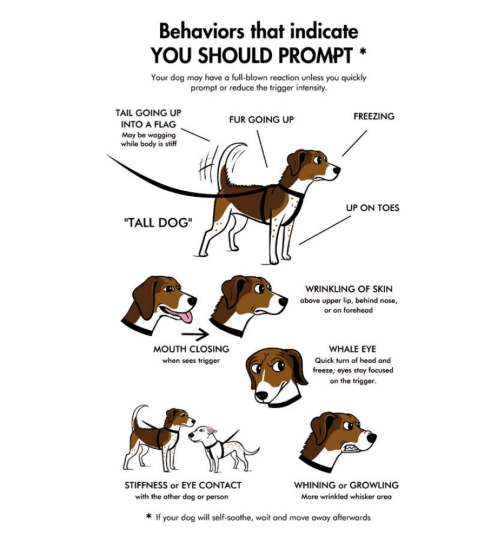

Stress makes it harder to unlearn fears. All the time, those flooded sinks are telling us that being safe is our number 1 concern and we should ‘save ourselves’. Fight. Flight. Freeze.

Stress sticks us in a rut and makes it harder for us to change our ways.

We go more easily to modal action patterns like chasing, circling or barking.

Hence compulsive disorders in dogs. I never see a compulsive barker without seeing a dog who isn’t coping well with stress. Nor a tail-chaser.

What do we typically do during a stressful time when something isn’t working? The same thing again, many more times, faster and more intensely— it becomes unimaginable that the usual isn’t working. If barking normally makes the bad stuff go away, it’s unimaginable that it’s not working, so our dogs bark more frequently, bark more loudly.

Stress also makes it hard to learn new responses. When we have a small sink, it makes it harder for us to learn. How rubbish is that?! The world conspires against us in so many ways. A small sink is biologically useful as it keeps you alive. It’s the bit that says ‘run away!’ if you’re in a war zone, or ‘fight!’ if you’re a mum protecting your children. It’s not biologically useful if you’ve had a car crash and now you have a panic attack every time anyone pulls up quickly at a junction. That last example is me, by the way. My sink shrank exponentially when a guy cut across me and caused a car accident.

Stress also lowers our inhibitions. It makes me want to get in street brawls with drivers who came to a squealing stop at a junction or pull out too soon onto a roundabout. Sometimes, I’m physically restraining myself from getting out of the car to yell at someone whose driving was marginally worse than the majority.

We see this in dogs too: dogs who usually have really good bite inhibition whose sink floods and then suddenly bite; dogs who normally have great recall and panic when they hear a gunshot; dogs who jump up more or bark more when they’re stressed out.

Sustained stress also makes us really bad at assessing risk. A guy coming to a roundabout at 5 miles faster than he should have, and being 2m closer than I’m happy with is not endangering my life. It’d be a fender bender at worst. Yet I react as if he’s got me at gunpoint and he’s Howling Mad Murdock in the A Team. A distant gunshot is nothing to most dogs. A storm isn’t life threatening. But small sink dogs aren’t good at assessing the risk of these.

Small, overflowing sinks are a recipe for displacement aggression as well. When I was fifteen, I watched a guy called Oggy punch a wall until his fist bled. Displaced aggression. I used to come home from work on a Friday and get into a fight with my boyfriend. Displaced aggression.

And we wonder why our dogs will turn around and bite us when stressed?

I was thinking about it the other day – every single contact a dog has made with their teeth on my body – has been ‘unpredictable’ in that there was no growling, no hard eye, no closed mouth, no lunges, no snarls. I’m sensible around dogs who have the slightest sign of fear or aggression. But I’ve had a fair few nips in over-excitement and on leaving the kennels or in handling dogs who are in pain. No warning kind of nips. Not loads and loads. I’m not some fool-hardy bite freak. But I’ve been on the receiving end of that displaced aggression in dogs enough times to know that stressful situations (leaving kennels, needing treatment, being in pain, being handled) can cause lowered bite inhibition and displaced aggression. Small sinks at work.

So when I say a dog has a small sink, what I mean is they don’t have the genes or the experience to cope with everything life throws at them. They ‘flood’ easily. Aggression or fearfulness are easy, automatic responses for them at times of stress.

Now you don’t have to live with this. Neither does your dog. You don’t have to say ‘oh well… small sink… can’t cope…’

You can do so much. You can limit triggers and stressors – the things that get the chemicals flooding in in the first place. You can also continue a gentle programme of gradual systematic desensitisation or exposure therapy. Those two things together can help your small sink dog cope with what life throws at them. Creating a safe, secure environment, teaching your dog autonomy and using both mental and physical exercise to help you ‘unblock’ the sink can also help your dog become more independent.

The very best way I’ve found of overcoming a small sink is to build a partnership. A dog who sees you as a secure base, who trusts that harm will never happen when you are there and who has a history of being safe when with you and when at home is a dog who is able to learn new strategies to cope with life. A dog who trusts you has a built-in overflow mechanism to help them cope. You. We all do better in life when we can depend on our friends and family. It’s no different for a dog. The right social systems and networks are enormous confidence boosts, and can help build resilience in your dog. You’re never going to make your Nervous Nellie into a Bombproof Brian, but the beauty of behaviour is that is doesn’t have to be fixed forever. Being realistic about what your dog can cope with and becoming a trusted base for them is a lifeline for many anxious, fearful or aggressive dogs. Life may have handed them a small sink, but it’s very helpful when your best friend is a plumber.

Is that one metaphor too far?

I think it probably is!