AND WHY IS IT RELEVANT FOR DOG TRAINERS?

Over the next three posts I’m going to be looking at all things Pavlovian and consider what their relevance is for dog training.

What’s the problem?

Pavlov is hugely relevant for dog training and yet I so often see mistakes in literature and on social media about what various concepts mean. It’s like it’s this whole mystical thing that almost nobody seems to really read about and so the myths perpetuate, thickening and strengthening each time they’re passed from one post to the next. If you’re working with an emotional dog, an over-aroused dog, a fearful dog, an aggressive dog, Pavlov isn’t sitting on your shoulder, as Bob Bailey would say, he’s actively messing with your training, interfering, making it less or more effective. I mean that dude – or the knowledge he unleashed on the world – is practically the reason your dog training life is not some neat little Skinner box where a click here and a treat there leads to impeccable, robotic behaviour.

What’s in a name?

Respondent conditioning is partly confusing because it has so many names. Classical conditioning, for one. AKA Pavlovian conditioning.

Why three names? Why not? Russians do, you know. Perhaps it’s just following on in the footsteps of Ivan Petrovich Pavlov. Perhaps we should really call it Pavlovian classical respondent conditioning.

It deserves a noble name, maybe.

It’s called Pavlovian conditioning sometimes after Pavlov, who investigated it. I guess others call it classical as a nod to stuff that came after, that it suggested a foundation, a cornerstone.

You know the story. Bells, meat and saliva.

Trying hard to do some work on the digestive system and the damn dogs kept dribbling when his assistants would walk in with a plate of meat… it fascinated Pavlov so much (having vexed him completely) that when he went to give his speech for the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine, he kept going on about this new form of learning he’d discovered and didn’t bother to talk as much about the digestive system that had been the topic of his study.

Worse still, some people call this type of learning associative learning. It’s also, just to be massively confusing, sometimes known as learning by association. I like this, but it kind of dumbs things down. I’m not a fan of dumbing things down or watering things down. It confuses things. It’s okay. You’re smart. I know you can cope.Like it’s helpful to have four names…

I call it respondent conditioning because it’s the science of responses. I’m going to stick with that throughout. It helps me remember that it’s about responding. Pavlov is all about our minds and bodies being at the beck and call of the world around us. We’re flotsam on the tide of life, helplessly responding even when we don’t want to, borne about by the currents around us and even within us.

What are unconditioned responses anyway?

So… respondent conditioning…

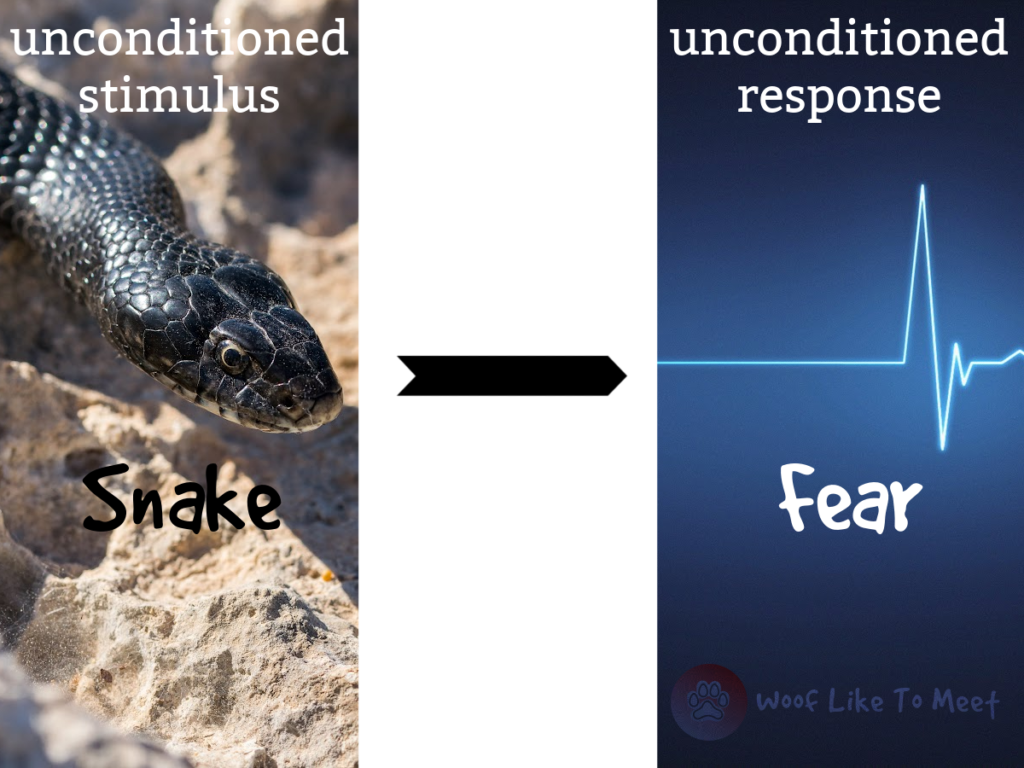

You know the drill. You take something your body can already do, like vary your pulse rate or your breathing or your salivary production. There’s going to be some science jargon here, but these are called unconditioned responses. Also, just for the sake of clarity, known as unconditional responses. What’s a suffix between friends?

Conditioning just really means learning. These are unconditioned because you’ve not learned them. You didn’t come out of the womb and have a lesson on how to breathe in and out, contrary to the things my sister and I told my brother. You didn’t have to learn how to salivate. Nobody runs classes on getting goosepimples. You can’t sign up for a TED talk on blushing. There aren’t Udemy courses for cats on how to right themselves as they jump. Prenatal classes aren’t teaching future mums how to have leaky nipples when the baby cries. You can’t buy Yawning for Dummies or An Idiot’s Guide to Gagging. There aren’t GCSEs and A levels in Better Allergic Reactions.

At first, Pavlov thought these were glandular or physiological responses only, but John Watson soon followed with some work about fear, and we started to realise it could be emotional responses too. You may not be able to buy Yawning for Dummies but you also can’t buy How To Feel Fear: A Book for Psychopaths.

Largely, these unconditioned responses are either reflexes, action patterns or emotions. A reflex isn’t actually the muscle or the eye blink or the saliva or the pupil dilation. It’s the relationship between the thing that causes the salivation (the unconditioned stimulus – you can handle the jargon) and the response (the unconditioned response).

This works for emotional responses too. I’m not going down the rabbit hole about whether emotions are real in animals or not. There haven’t been 70 years (and more) of abusive experiments cutting out bits of animal brains, giving them drugs, attaching printer cables to their heads and submitting them to fMRI scanners for us to say that animals don’t have emotions. They have the circuitry. I’m in the camp that is now asking if you can prove that animals don’t have emotions, not the one saying ‘but they can’t tell us they have emotions!’

Now of course, you may feel that snakes are actually not an unconditioned stimulus, and you’d have some legway in an argument. However, it’s very easy to condition fears to certain things. For instance, in experiments where researchers were seeing how easy it was to teach monkeys to be afraid of snakes or flowers, and how long those learned responses lasted, it turned out that monkeys are very good at learning to be fearful of snakes and it’s really hard to teach them not to be, and it’s fairly easy to teach them to be afraid of flowers, but really easy to stop them fearing flowers too. You can see the work of psychologists Susan Mineka and Michael Cook from the late 1980s on this and it’s fascinating.

You can see here an unconditioned response to a shedded snakeskin that freaked Lidy out. It doesn’t have the same effect on Heston, who’s in the ‘can I eat it?’ phase of life and isn’t fearful of anything except vets.

As you see here, we’re crossing into the realm of learned responses, though. The point of unconditioned responses is that they are highly stereotypical and they are found in most members of the species. If I want to know if something is an unconditioned respondent behaviour, I ask myself if most members of the species do it.

Of course, these unconditioned responses are age-dependent. Some fade as we get older. Others appear as we age. A pre-pubescent person doesn’t (usually) produce milk. That’s an age-dependent response. Your reflexes get slower as you age as well, which is why you need to re-take your driving test when you hit a certain point (and, maybe, as discussed by my brother and I on Friday, why older people – including us – drive slower as an instinctive awareness that our lightning fast reflexes are fading…)

While respondent behaviours – particularly the simple ones like reflexes – are highly stereotypical across a species, that’s not to say they don’t vary. They can be more intense. They may look a little different. They may be quicker in some members of the species and slower in others. They might appear when we’re different ages. Puberty does not hit us all on the first day of our 13th birthday, does it?

These behaviours are often adaptive. That’s to say, they help us survive better. Being able to right yourself as you fall has clearly adaptive value to a squirrel and a cat, just as instinctively sticking your hands out to break your fall (and save your indispensible head) does for humans.

Often, the only reason that we won’t have a response like this is because we’re physically unable to. That’s to say, we don’t have the right hormones at the right moment, or we are actually and physically unable to do so because of injury. Think of David Bowie’s irregular eye, for example, where his pupil was incapable of much dilation or contraction as the result of a condition called anisocoria. Most of us human beings, though, have pupils that dilate in certain conditions and contract in others. There may be lots of stimuli that cause that behaviour, from internal ones like hormones and neurotransmitters, to ingested ones like drugs to external ones like light conditions. Take amphetamines and your pupils will dilate, whether you’re thirteen or fifty, male or female, no matter where in the world you come from.

Just like our appearance, our reflexes can also be inherited. I don’t have much of a gag reflex (weird, I know) and although I’ve not checked out my siblings or parents, I wouldn’t be surprised if one of my parents didn’t either. Just to be clear, I don’t like things being stuck down my throat but it doesn’t make me have a pharyngeal reaction. By the way, pharyngeal reactions are adaptive: you’re a hell of a lot less likely to choke to death than I am. Perhaps that’s why I’m convinced I’ll die alone having choked on a scone. You may also have a very sensitive gag reflex – you’d know if you’ve had a lot of Covid tests recently – or you may also have desensitised your pharyngeal response. Let’s not go there, shall we? I don’t care what you do in your private live with other consenting adults.

Other behaviours are more complex than these simple reflexes. Such behaviours in animals (and humans) may involve mating, mothering and eating. They’re not as rigid, partly because they’re usually a behaviour chain, but also because they need variation. We’re not birds dancing some weird mating dance or trapdoor spiders who always get food in the same way. Survival benefits from adaptability in terms of reproduction, parenting and eating, among others. Thus, the mate-attracting behaviour of the male Mancunian at his sexual prime may not be exactly the same as that of the refined Parisian, but larger behaviours are more subject to environmental influence. Dudes do what works. And dogs do what works. What works will largely depend on the circumstance. If covering yourself with fake tan, pumping up your muscles and growing a man bun gets you dates with the kind of girls who float your boat, then that’s what you’ll do. We aren’t as free-minded as we like to think we are. In tests of attractiveness, people shown photo sets where the subjects had dilated pupils rated them as more attractive than photo sets of the same subjects with contracted pupils. So much for choice, hey?

So… to recap so far, reflexes are:

- relationships between a stimulus and a response

- relatively simple

- present at birth, or

- appearing at relatively predictable points in our development

- evident across a whole species

- adaptive

- usually only absent in those physically incapable of producing them

- inherited

And some unconditioned responses are more varied and more complicated, but still a relationship between X stimulus and Y response.

Where does conditioning come in?

Through life, our brains happily busy themselves in the proeess of associating other stuff with those unconditioned stimuli. This is learning. For literally no good reason I can see, Pavlov decided to call this conditioning and not learning. Well, he didn’t, because he wrote in Russian and there weren’t agreements among his translators, so we’re left with words that don’t facilitate ease of understanding.

However, conditioning means we’re learning. We become selective and we narrow down, on the one hand, and on the other, we learn more things that cause the same response.

Perhaps it’s good that he stayed away from any Russian words that would easily be translated as learning. We humans think of learning as a conscious, voluntary process. Pavlovian conditioning might not be that at all, necessarily.

Largely speaking, though, we become more selective about certain stimuli that cause particular responses. Thus, we might end up with a very narrow little peccadillo for tall men with dark eyes and sharp cheekbones, or eyes that have a certain naughty twinkle, or women with flaming locks of long auburn hair. It could be something as weird as the turn of an ankle or the shape of a wrist. It could be a smell or a movement or even a sound. Don’t believe me? Find me a Canadian or a Cumbrian saying ‘oceans’ and watch me start batting my eyelashes. Sean Bean’s Sheffield accent? Hello, Mr Sharpe! As soon as we see, hear, smell or even feel certain stimuli that float our boats… Bam…. response. Biologists call these things sign stimuli or, in the spirit of science, innate releasing mechanisms. Are you really science if you don’t have two names?

Thankfully, humans are built with a powerful override that helps us control ourselves in the presence of such sign stimuli. Not as much as you’d think, which is why a handsome tall man will usually find life in politics or business easier than any other, but just enough to stop us all throwing ourselves at people whenever anyone over 6 foot comes a-striding in. Not as bad as some poor creatures though. Poor male turkeys who’ll try to mate a female turkey head on a stick, for example…

For dogs, they have plenty of sign stimuli, from pheromonal ones that signal a female is in season to the presentation of meat that elicits dribbling and, perhaps, the flash of light and movement that signals the presence of prey.

Those are the ones we’re born with. The unconditioned ones. But animals also learn to become more discriminatory and their unconditioned responses might weaken. For instance, my dog Heston is an intact male. He doesn’t get excited by all intact and in season females. We’ve had two or three in-season female guests who definitely did not float his boat.

Others, we acquire as we go through life. We learn to love the taste of Marmite (or not) and the sounds of Sean Bean saying stuff in purest Yorkshireness and the smell of our nanas and the touch of a loved one….

For our dogs, they might acquire a taste for certain things but they also might learn new stimuli that also cause a physiological or emotional response.

For Lidy, she’s learned more things that cause her to feel afraid:

As Minecka and Cook point out, some of those will have been easily learned because they’re typical things that threaten a dog’s survival, including predators running at you, loud noises and other dogs.

Unfortunately, easily learned equals hard to lose.

Many people will point out that during a particularly sensitive period of our development, we have the opportunity to habituate or get used to unpleasant or threatening stimuli. A well-socialised dog will learn that loud noises are not life-threatening, that joggers will pass you by, that fireworks are not the world imploding and that vets aren’t going to kill you.

Don’t judge dogs if you won’t get your shots, are phobic about needles, hate the dentist, hate flying or won’t speak in front of people.

Dogs have typically learned to associate these novel stimuli with bad stuff like pain or fearfulness. Or, perhaps others might argue that dogs haven’t learned not to associate these novel stimuli with bad stuff.

Bad stuff can be so powerful that I know dogs who have associated logs crackling, microwaves beeping, wasps and flies buzzing about, car journeys and even the sound of cans opening with negative experiences. These conditioned stimuli come to predict bad stuff, like pain or negative emotional states.

Again, don’t be judgey. I used to drive home and work from home when I saw the car of a bully in the car park, I’d walk another route if I saw one particular dog in the yard, and I’d happily avoid certain people who have come to predict a feeling of disgust or fear.

This type of learning – respondent conditioning – needs two things to happen.

The first is contingency. The first thing needs to reliably predict the second.

The second is contiguity. The first thing needs to be relatively close in time to the second.

It’s not all bad, though.

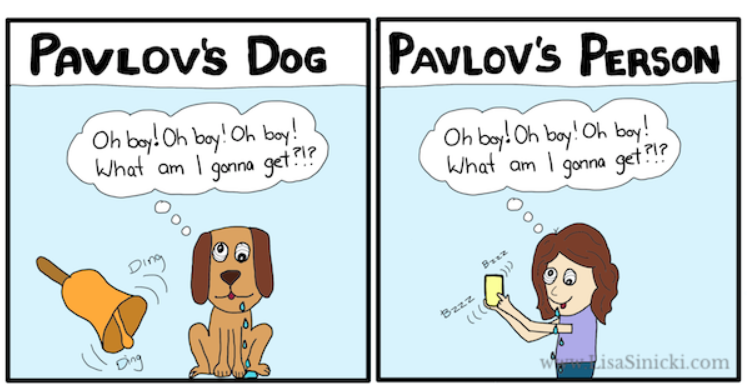

We also learn to associate neutral stuff with good stuff too. We go through life picking up tips that good stuff is about to happen, and that makes neutral stuff feel good too.

That’s what life is about… learning more stuff that creates those same feelings. Life would be pretty lame if only Sean Bean could make me sigh like a schoolgirl at a boy band concert… and thus, Keanu Reeves and Jim Caviezel and Dave Grohl and Bob Mortimer all still get my heart beating. And some actual people in actual real life too, just in case you think I only live in TV land. Thank goodness.

Likewise (and unfortunately) it’s not just Marmite that makes me salivate, but onion rings and hummus and stir fry and a good curry and syrup pudding and caramel ice cream… and they don’t just make me salivate. They make me feel better. For a moment, anyway. It’s not just a buttered scone but a mouthful of comfort.

And I wonder why I’ve so little willpower!

These things are known as conditioned stimuli: things we’ve learned through life that elicit some innate reaction that nobody ever had to teach me how to have. Nobody needed to teach me to learn to salivate. I, luckily, was born knowing that. But I did need to learn that churros were yum and anchovies were not yum. Also, some things grew on me more slowly.

Behaviour scientists use the word elicit when they talk about respondent conditioning. The stimulus elicits the response. It’s not a very good word because it doesn’t really suggest the power of those stimuli to really cause that response. I mean, it’s not an ‘oh well, might as well!’ from your body. It’s a ‘You said jump, I said how high?’ thing. Your body doesn’t get much of a choice. Take amphetamines, your eyes will dilate, kind of thing.

It’s not just that you can will yourself to stop responding just because you want to. I mean, send in Keanu if you must and even if you give me a million pounds, I’m not sure I would be able to stop myself a) giggling if he looks at me b) batting my lashes at him c) blushing when he speaks to me and d) flirting like it was going out of fashion.

Respondent conditioning is some powerful stuff.

These responses are complicated, all right.

Our dogs also have these responses. Heston gets sexy ears when certain lady dogs flirt with him, and he has learned a flehman response to a number of lady dogs’ urine. Both of my dogs get excited when they see a harness, a bowl, a Kong, a brush, a lead, the car keys, my boots. Both get excited when the alarm goes, when I go to the toilet first thing in the morning, when I move my handbag. Lidy hides when things bang and there are fireworks or gun shots or thunder and Heston hides from nothing except the vet.

Learning by association is a powerful thing.

It’s also super easy. You just need to pair stuff up. It needs to be relatively timely and the second thing needs to depend on the first. Contingent and contiguous.

Walks depend on me having been to the toilet first. They depend on me putting my boots on. Car trips depend on me picking my handbag up and my car keys. Brushing depends on me holding the brush. Games depend on me picking up a toy. Dinner time depends on me getting the bowls and feeders out.

These things in themselves come to elicit the same bodily reaction, or frustration, or even anticipation.

Then there’s something called second-order conditioning, where the thing before the thing comes to predict the other thing. Like seeing the golden Arches predicts MacDonalds predicts Happy Meals for kids which predict salivation… and me going to the toilet predicts I’ll put my boots on predicts I’ll take the dogs out for a walk.

Life is a chain of associations.

However, sometimes those associations can be over-exciting. The smell of cats is intensely exciting for one of my dogs. The smell of deer and boar is for my other. The smell of other dogs can be a threat. You can read all about why this is problematic in my post about dogs thinking fast and slow. The flash of light or the flash of movement of a car on the horizon can set off the same behaviours as a dog chasing prey.

Those sign stimuli that can elicit a response can be surprisingly brief and surprisingly powerful. I can’t blame dogs for feeling the urge to chase a car when I get goosepimples within two words of Unchained Melody and I’m weeping by the end of the first verse.

Often, these associations formed by respondent conditioning are just stuff that helps us get through the day. Other times, they can become phobias or responses that interfere with our welfare. For our dogs, they can be so powerful that they can disrupt training and derail a ‘normal’ existence, whatever that may be. If your pathological response is to be hijacked into barking in a frenzy for ten minutes just because you think you might have seen another dog, that’s one response that is definitely not adaptive. If your pathological need to control motion is so strong that it will force you to run into a stream of traffic, that is not adaptive. If you can’t rest for hours because a microwave binged, that is not adaptive.

Luckily, we have ways to help us overcome those conditioned responses. Respondent counterconditioning is a powerful tool we can use to help us move towards a more healthy response if we’re feeling like flotsam on the tide of life, unable to choose our own more adaptive behaviour, at the beck and call of the universe and whatever it tells us to do. Next week, I’ll take a good long look at respondent counterconditioning and explain why it’s such a useful tool for anyone looking to help their dog (and even themselves) cope better. If your dog is at the mercy of the world around them, hijacked by fear, forced into reactivity, overly sensitive to the stimuli they’re surrounded by, desperately trying to chase anything that even hints at moving, then respondent counterconditioning will be your powerful ally.

Don’t forget to sign up for email alerts if you want these posts delivered to your inbox.

My book for dog trainers is available on Amazon in ebook and paperback form. If you’ve already read it, could you be so kind as to leave me your thoughts to help others decide to buy it?