Apologies for an insanely long absence. Sadly, dissertations don’t write themselves and they take over your life if you let them.

I’ve spent the best part of the last six months focused on assessment. Be it human or canine, diagnosis and evaluation isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. The last week has helped me focus very much on labels, and how they can be useful as well as how they can be completely unhelpful. A phonecall yesterday helped really make that very clear.

I suspect, too, that it is a big part of why my main focus – aggression – is so often labelled ‘dominance aggression’ and a rank reduction programme is put in place. It’s such a neat term. It practically covers everything and the treatment is always the same. It’s a snake-oil treatment – one with as many consequences. It avoids the messy practicality of trying to identify causes and effects.

Yesterday’s phonecall made it really clear why quick labels often don’t work.

In the back of my head, I always hear the voice of one particular dog ‘expert’, and I heard it very strongly yesterday when I was listening to what was being described. I could imagine this ‘expert’ saying ‘dominance aggression’ after ten minutes and deciding that the pack needed sorting out and one of the dogs, if not both, needed putting in their place.

Yet as you’ll see, it’s so much more complicated than that.

The situation involves two people, three dogs and a cat. There’s an elderly sterilised female, an elderly cat, an uncastrated seven-year-old collie cross (Pip) and an uncastrated four-year-old dachshund x terrier (Harry). Recently, when the human couple are together and the cat has come in, Pip and Harry have ended up having a scrap. As so often happens, the owners separated them and got hurt for their peace-keeping efforts. Hearing about them made it very clear that there aren’t always simple explanations and how a number of factors can sometimes combine to create a “perfect storm”.

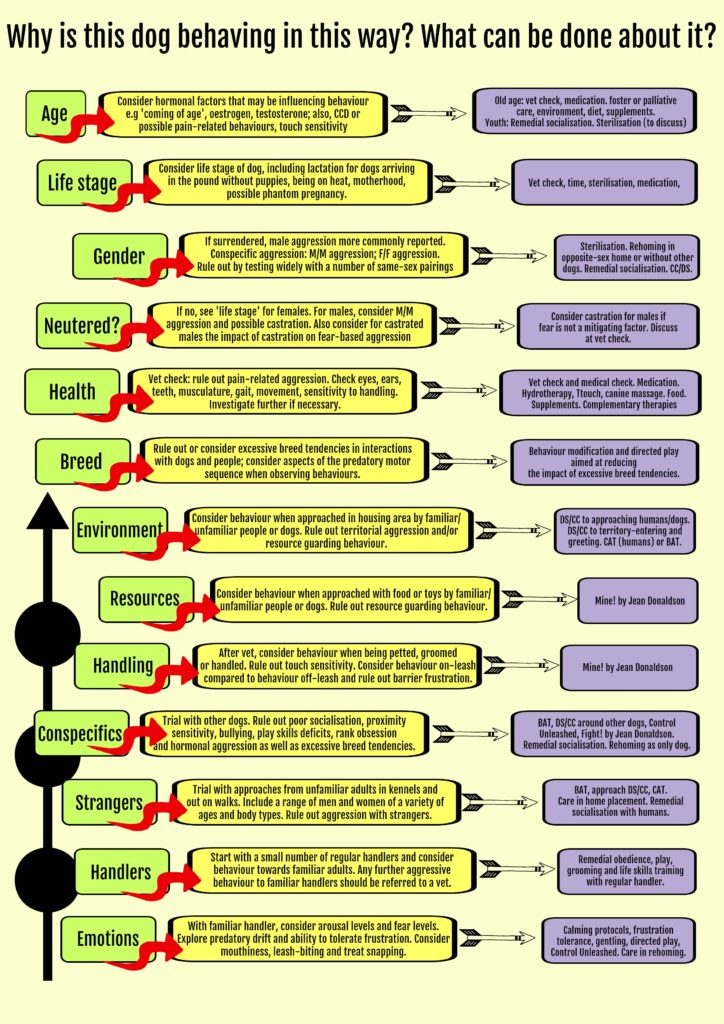

In shelters, we need quick assessment methods to help us understand the situation. As part of my dissertation, I drew up this simplistic flow-chart to help make decisions about what is influencing aggression and what we can do to help work it out. Identify the triggers and you are half-way to working out a behaviour modification programme. The flowchart was designed to help quick identification of common triggers and suggest tried-and-tested modification programmes to help.

This is necessary to some degree in shelters where dogs are adopted quickly. This flowchart helps identify and rule out some common situations in which aggression may present itself, and therefore suggest some tried-and-tested modifications. What it does not do is extend to familiar dogs or familiar humans in familiar situations. Still, it works in roughly the same way. Rule out medical/physiological/biological. Rule out species-specific behaviour. Rule out individual aspects.

You can see why flowcharts like this alongside simple assessments can fail when I tell you a little about the situation. described yesterday where are perhaps twenty triggers or more that could all be weighing in and creating a breeding ground for hostility.

First, life stage. The elderly female has had pyrometra and is now on hormone tablets. That may or may not be affecting things. Even sterilised females are ‘smelly’. If they weren’t, my dog Heston wouldn’t lick Tilly’s wee and do the Hannibal Lecter thing. And Effel, my castrated foster beauceron, wouldn’t feel like humping her. For Pip and Harry who are both intact, you’ve got male-male testosterone issues to consider, as well as the hormone status of the older girl.

Add to that Harry’s recent adulthood and he may well feel like he can challenge Pip as an equal. Without coming back to pack rank issues, which complicate things no end especially in dogs who do not exhibit an easy-to-identify or fixed pack rank, it may be that the age and declining health of the older female may be having an influence as well as the increased hormones, other than adding a degree of competition to the air over social order. She could also be grumpier which could also be affecting household tensions.

Add to that the health of the owners… which is another complicating factor that may be having an influence… Dogs can certainly detect human health and hormones, but there is no real research into how that affects the dog’s behaviour. On a practical level, when we ourselves don’t feel on top form, our wards can take advantage of that. At a simple level, structures are less secure, routines less reliable, and the order of things is thrown into chaos. So that’s a possible factor too.

I think it is very likely that the health of the elderly female dog is having an influence on the situation, since the situation has worsened with her health. But it could also be as a result of the adulthood of the younger dog that has coincided with this, and also the health of the owners. I’m going to keep saying “a perfect storm”, because I think that’s often what situations are: a unique situation that is one in which several interlinked factors have a bearing. However, no matter what I think, it is an opinion only. I’d want to compare the house without these factors to the house with these factors, and that is just not possible.

Gender can be an influence, as can neuter status. By the way, I read almost 100 different studies of the effect of castration on behaviour for my dissertation. That was fun. But boy hormones could be playing a part. That’s not to say castration is a solution, especially since Pip is very fearful. Castration can make fearful dogs worse, and so to castrate him could worsen his behaviour. Castrate one without castrating the other and you’ve got potential fallout without any guarantee of success in ‘curing’ the fights. At best, castration may resolve about two-thirds of sexual behaviour such as wandering, territorial marking and humping, but it is far from being a given, and that is only a result if hormones were indeed a factor in the behaviour. Castration is not a cure-all. So the situation could be influenced by male hormones (and those rogue female ones from the older girl).

Breed and biology could be factors. Though the younger dog is smaller, he is a dachshund x terrier mix… two breeds with a long and intact instinctive sequence of behaviours. A pack of terriers is a different dynamic than a pack of beagles. Terriers can be ‘dog-hot’ if their breed tendencies are excessive, and they are hard-wired to get off on the struggles of other animals. Excessive breed tendencies can mean that some terriers get a biological buzz from certain behaviours. So that could also be a factor. Harry is also a resource-guarder, which can relate to breed, but can also relate to other things. He is territorial over beds and space, collects toys and doesn’t let Pip play with them…. factors which suggest other individual characteristics as well.

The environment is a huge factor influencing the fights between the two dogs. These fights are occurring in familiar terrain, in the same places, and only when both owners are present. The arrival of the cat is also a factor. She is also elderly and having terrain wars, so she is coming in more, which could in turn be having an influence on the boys. Pip, being a collie, is attracted to the cat’s movement, and Harry, being resource-guardy, could consider the cat to be his rightful possession or is trying to eliminate competition from Pip over who has access to the cat. Not only that, both dogs are ‘owned’ by a different member of the couple and there are some indications that Harry is guarding the lady owner. Since the fights don’t happen when only one of the human couple are present, that too is interesting. It suggests to me that there’s a changing dynamic in the room when both adults are present. Everyone is more tense. Dogs are great distinguishers. They are good at knowing ‘I get biscuits from you, but not from you’ or ‘that post-lady in the yellow van always goes away when I bark, and that one in the white van brings us a parcel full of treats, food and toys’. They know there are different rules for different people. If they know that with the man, they do things one way and with the lady, things are a little different, that too can give rise to confusion when those two worlds collide.

I’m not even half-way through yet and there are already a half-dozen factors that could be influencing the dog fights!

Is Harry suddenly launching a bid to be ‘top dog’? Who knows? Unlikely, given all the other factors.

But then you also have individual personalities. Harry is a dog who (like dachshunds and terriers can be!) finds ways to get his own way. He is confident, but his resource guarding suggests that this is all a bluff. A truly confident dog doesn’t feel insecure that another dog will nick his toys. Pip is naturally nervous and fearful. For a dog that is more fearful or passive by nature, it is easy for a confident dog (or a dog filled with false confidence, or one who has decided he really, really wants access to a given resource) to take advantage of that. My dog Tilly is a great example. She may be 12kg, but she will happily go over to another dog’s bowl and snaffle food if they take their eye off the game. That bowl is then her bowl and heaven help you if you want it back.

And you’ve got relationships. The dogs don’t like each other and there are times when their general dislike spills over, particularly in moments of tension and excitement.

How many potential causes is that?!

When you can’t pin down a cause, you have to go with what you can see.

What can be seen? When both adults are present and the cat comes in, Pip and Harry have a fight.

The fight in itself gives us information and a caution. It is noisy and never results in damage (although the humans have intervened) which suggests it’s ritualised – a way of sorting out differences without harming each other. It suggests a fair prognosis. That said, Harry is 5kg and Pip is 20. Harry could easily get hurt, though he hasn’t been already.

Regardless of cause, a behaviour management programme will still work. There are options here.

One option is to manage the situation. This is what I have suggested. There are too many factors that could be making this perfect storm of conditions right now that are likely to change: the changing health of the elderly female, the health of the cat, the current health of the owners. Harry is the instigator of the attacks and his movement can be managed. He is already crate-trained and keeping him on a lead for a couple of weeks in the house will allow the couple to keep him from escalating behaviours with Pip. My dog Heston doesn’t get on well with my foster dog Effel, but I’m not doing anything other than managing it, because Effel is not a permanent fixture. That said, I intervene when Effel is being a doggie dick. It is not good for him to run past Heston and block him, to bodycheck him at food times, to stare at him when Heston is resting or to try and bully Heston out of his bed. If he is being a knob with Heston, it is up to me to manage that unless I want 75kg of dog fight. That said, Heston does a good job of restraining himself on the whole, but there are times when Effel’s doggie knobhead tendencies go too far. Leads and obedience are the best things here, as well as being aware of canine manners. Stares, blocking access and hard postures are very rude canine behaviours so that is something I watch for. Training new and better responses is the end-goal, but not easy if you are in circumstances that will no doubt change further.

I would also make sure that if Harry was not directly and actively supervised, he is on a lead or in a crate because the consequence to him of going too far would be fatal. Pip needs time away from Harry, and vice versa. You know how it is when you are in each other’s space all day long: cabin fever affects dogs too, I’m sure. Tensions rise and tempers flare.

Were the dogs likely to have to live in similar conditions for a long time, either a lifetime management plan or some serious emotional changes would need to take place. That is a work and a half. That’d take a book in itself to outline the programme, the rationale and the protocols.

There are certainly other things that the owners can do to reduce stress in the home, too, and I think that would take up another book alongside one on active behaviour modification.

As you can see, though, assessing the causes of aggression can be complicated if not entirely impossible. It’s rarely one single factor that is causing a problem, though it’s nice when it is. There are times when it is easy to identify the exact trigger of a behaviour, but there are also times when it is a “perfect storm” of possible environmental triggers. There are no simple ways to assess cases like this easily and because it’s not easy to pinpoint one single cause, it’s not easy to identify one single solution. Labels in this circumstance would be unhelpful and since several of the factors are going to change, making some small changes to ensure the dogs don’t hurt each other is a valid approach in itself.