There are many times when I’ve started working with a new client and they’ve told me their dog is not treat-motivated. They won’t eat outside, they won’t take treats. Last week, I had a client say exactly the same.

“I don’t know how we’re going to do any work. She doesn’t take treats!”

Lots of guardians want to know what to do in this case. They want to know if there other magical ways of working that we can use instead?

Some dogs, it is true, are very toy-oriented. For those dogs, it’s easy to sub in a toy instead. The problem is that for many dogs, even their best toy won’t work in the ways their guardians want it to: to build behaviour change.

Not only that, toys can be counter-productive, depending on what you’re doing and depending on your dog. It also may depend on the dog’s age, as dogs get less toy-oriented as they get older. Personally, I love dogs who’ll work for food, and they’ll work for toys, and they’ll work for an enthusiastic ‘What a good dog!’ and a bit of massage and for functional reinforcers. I like my dogs to have a very wide repertoire of stuff I can keep in our toolkit so I’ve got the right tool to build the behaviour I want to see. Toys are great for feeling good, for building up energy levels, for building relationships. They aren’t good for calming dogs down. So if you want calm behaviours, you’re going to have to have a dog who has got a lot of self-control if you’re using toys.

Now of course, that’s possible. But if you’re excited anyway, adding a toy to the mix isn’t going to make it easy on the dog to calm down. That is some high-grade control.

And we’re so human that we can’t steer ourselves away from the fact our words are just not that interesting to a dog. I mean my dogs do seem to like ‘What a great dog!’ but I don’t have to guess if they like steak.

Invariably, ‘dogs who are not treat-oriented’ are dogs who’ve got problem behaviours outside the home, where you’d really like them to be treat-oriented. You know – dogs who pull, dogs who don’t have recall, dogs who frighten old ladies by barking… If you didn’t have a problem, you wouldn’t care that your dog was not interested in food outside the home.

So what is the problem?

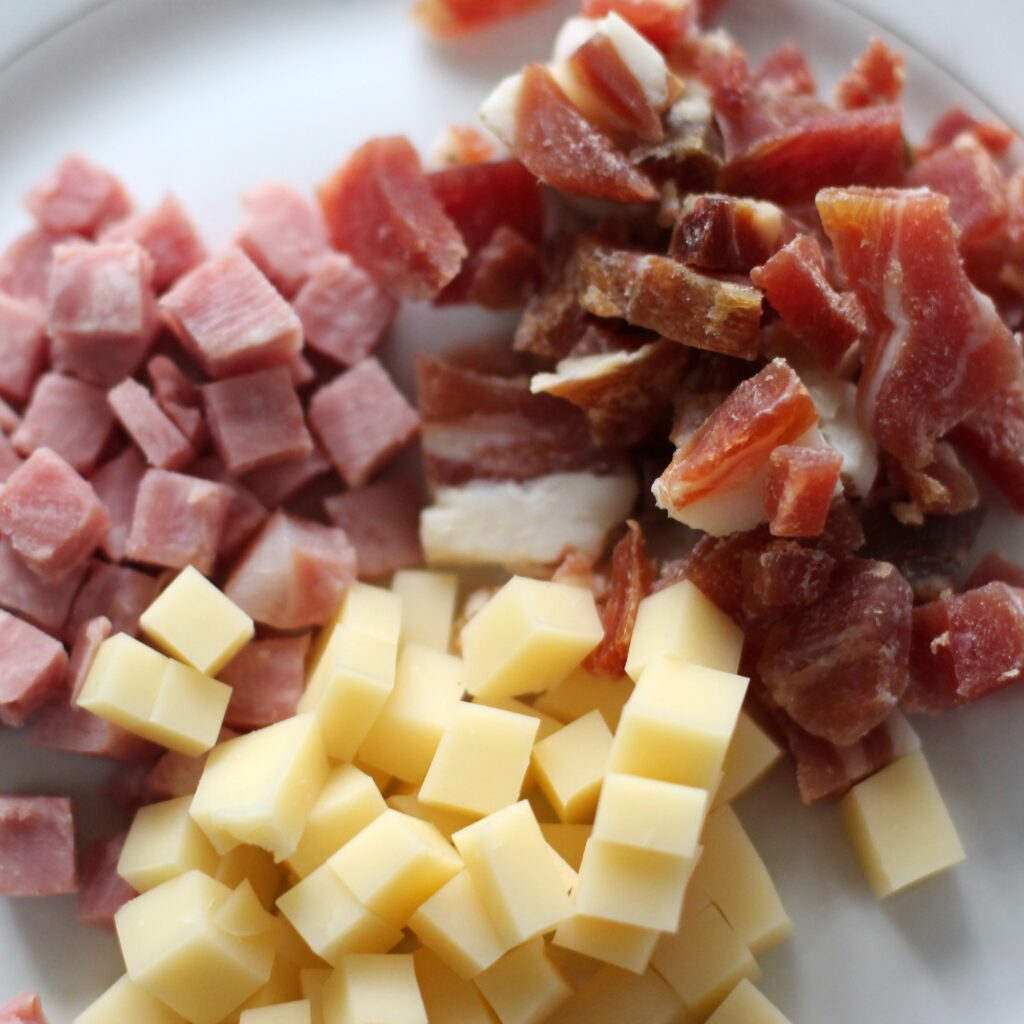

#1 Using low grade food

A very high proportion of guardians who say their dog isn’t treat oriented are using packets of ‘treats’ they picked up from the dog food shelf in the supermarket. Following an accidental taste test, I can confirm that these taste worse than actual dog biscuits. They taste of flour. They’re mealy, chewy, boring versions of Jacobs’ Cream Crackers. Now I love a cream cracker. With stuff on it. Naked cracker? Not so much. Three of them? Pass me a glass of water, please.

A surprising number of humans are also touchy about their dog getting ‘human’ stuff. It’s odd, because ‘human’ stuff is very subjective. I’m a vegan living in rural France. Brains, innards, kidneys, livers, veal, goat, horse, rabbit, duck, paté, tripe, blood sausage, heart and even something called andouillette, which is made with the lower end of the colon and smells like it too. Much of what your average French person considers delectable would turn the stomachs of other nations. ‘Human’ food is a cultural concept that we need to ditch if we want our dogs to find food valuable.

So often, I find that dogs who I’ve been told are ‘not treat oriented’ are actually highly motivated to work for food – when that food is great food. This is by far and away the biggest error I find guardians making – expecting floury baked biscuits with a long shelf life to be as good as something from the refrigerator.

#2 Not having an eating habit

Another reason people tell me their dog isn’t treat motivated is that in fact, their dog is very set in habits determined by their humans. They’re just not used to eating on the move. If we’ve got very set meal times, then we may find our dogs struggling to eat beyond the bowl. They’re not used to snacking. They’re certainly not used to snacking outside the house.

I know how this is. I grew up in the 1970s when eating in the streets in the UK was disapproved of by my grandparents. If you ate outside, you had tablecloths and silverware and goblets (I kid you not) and salt and pepper in Tupperware. And you ate at lunchtime. With cutlery.

Rural France still works on these principles. Sure, people eat on the trot, but traditional supermarkets are empty at lunch time and if you try to get something to eat at 1.30 from a rural restaurant, good luck to you. I know I certainly didn’t snack in the same ways as I do now, or eat on the move.

Having an ‘any place, any time’ dog who has the habit of eating in public is a behaviour you can teach, a habit you can cultivate. If you want your dog to sit and eat treats in the vet, don’t leave it to chance and hope they will. You can start by using the bowl less. I’m not a fan of immediately switching to ‘any place, any time’ with lots of enrichment toys. My nana is in a nursing home and I know how important food rituals are and how stressful they can be when they are disrupted. I don’t want my dogs to be anxious because they don’t know when the next meal will arrive.

Nor do I want dogs who have never had to forage or rummage to have to switch. We have a number of dogs at the shelter who find it impossible to eat outside their normal routine after surrender – simply because they’ve been hand-fed or they expect food at particular times. Some dogs just aren’t even used to a bowl. We have to accept if we’ve got a dog who we’ve turned into a slave to routine that it’ll be stressful to disrupt that. Also, I don’t believe every single thing we eat should be difficult to access or we should have to work for. The relief of just being able to eat is not to be sniffed at.

However, if you’ve got dogs who’ve never taken a treat from you, or who don’t know what food toys are, then a little less in the bowl and a little more in toys can be a start. Then work from there.

Dogs who can eat any place and any time are a gift to train. Just seen a deer? If you can eat, great. In the vet? Great if you can take food. Stressful experience? If you are able to eat, then training can happen.

But we don’t get ‘any place, any time’ dogs without building that skill.

Also, and this is really important, habits are born when we are young. The same goes for our palate. If dogs aren’t exposed to a lot of food when young, you might not be offering them things they find appealing. Sure, this is going to be true for carrots and banana if your dog was a strictly meat kind of puppy, but that can also be true for tastes and textures we would expect dogs to just like, such as steak. There are also dogs who like to savour the good stuff and it is possible to have food that dogs want to enjoy. One of mine enjoys smelling novel foods offered to her and will often go away and eat new things slowly, even if they’re very full of meaty goodness. It’s always worth ruling out problems with the things your dog has been exposed to in their life. I even know dogs who were punished for begging or stealing ‘human’ food who are then frightened by human food. One of my guys was like this: stale baguette was terrifying!

#3 Being in a state of stress

The mammalian body is built with two systems: voluntary actions and involuntary actions. The involuntary bit is split into two: the parasympathetic and the sympathetic nervous system. Remember back in high school biology where you learned about homeostasis? The Rest-and-Digest mode? That’s the parasympathetic bit. And Fight-or-Flight mode? That’s the sympathetic bit. Now it’s not like one works and the other stops – more of a sliding scale, but, as Robert Sapolsky says, if you’re a zebra and you’re being chased by a lion, you aren’t thinking of digesting your lunch or where your next meal will come from.

Fight-or-flight mode (well, it’s more complicated than that, but let’s stick with simple for now) can mean you’re in chronic stress – like some of the dogs in our shelter – or can mean acute stress. Dogs in states of acute stress tend not to be eaters. If your dog can normally eat food but when they’re faced with a scary clown, they won’t take a treat, that tells you that your dog’s body is in a state of acute stress. Conversely, chronic stress can affect our appetite. Some people stop eating; others eat more. Fat me is stressed me. I self-medicate with food when chronically stressed. Other people lose their appetite. So you may find your dog snatching and even eating more in chronic stress, but again, if your dog normally has a fairly healthy appetite, then you may be asking too much of them and you may need to put a bit of distance in there before your dog feels interested again in food.

Stress isn’t all bad. Homeostasis, Rest-and-Digest, can be interrupted when we having mating opportunities, when we’re engaged in social activity or when we are on the hunt. Doing exciting things can make us lose our appetite.

Many dogs hit the outside world with the fervor of a kid let loose in a free theme park. It’s all so much fun. It’s all so much more interesting than sleeping on the sofa or hanging around on the patio. Many of us struggle with our dogs because we’re battling with a very stimulating outside world and our dog has no history of focusing on us or eating at such a time, and it also goes against what they’re actually interested in doing. The good thing is that food can be interesting to smell and taste. Theme parks also have busy food stands. There’s no reason an excited dog can’t also enjoy the odd hot dog. That said, if you’re asking for complex behaviours, don’t be surprised if they just can’t do very much. Today, I cued Lidy to ‘touch’ three times. It was too much. I chucked her a treat and said ‘Find it!’ and she could manage that. Touching my hand with her nose was too big an ask. Eating, however, was not.

What happens when we ask for a simpler behaviour is that the dog often then re-engages with us. I asked for a hand touch again straight after and got one. If one thing is too hard, go easy and then build up to the hard thing in progressive stages.

#4 Being sick or feeling unwell

Many guardians fail to recognise that their dog is too stressed to eat and confuse that with not being food oriented. Sadly, they may also fail to do the same with a dog who is getting older or is not well. This can even happen on medication. Some medications upset stomachs, and it’s not a surprise if the dog doesn’t feel like performing for you in return for a snack. If your dog used to be food oriented but isn’t any more, this might be a good time for a check up.

This can also affect their preference for treats. If your dog is refusing one texture of treat, it’s worthwhile trying with another. And just as dogs might not be able to do complex behaviours, I sometimes find that this involves eating itself. The more complex the eating (harder, longer, less appetising chews) can be refused where they’ll still opt for easier eating. If in doubt, I go with potted meat mixed in with gravy so that it doesn’t even involve much chewing.

Of course, if you’re old and your teeth hurt or you don’t want to do what you’re being asked because it’s painful, then you might refuse food too. I see a lot of dogs asked to sit who just feel uncomfortable doing it. Sit is one behaviour I never ask for. My dogs can and do sit, and they do so of their own volition, but I don’t ask for it. We may also need to think about whether our dog is refusing because they don’t want to do the behaviour that leads to the treat. This is never because they’re stubborn. I’d be checking #1-3 first.

A sore mouth, throat, tummy, gut or bum can also lead to a dog who might not eat when they have in the past. Even ear issues can be worsened if you’re asked to chew. Not sure if you’ve ever tried to eat when you’ve got a headache or earache – it’s not the best. Hormonal issues can also play into this, so if got a dog who’s suddenly stopped eating or has gradually lost their appetite, it’s worth mentioning it to your vet.

#5 They’re not hungry

I scoff at this because… dogs… but then I’ve never lived with tiny dogs. Most of my dogs have been 25kg or more and there was always room for a snack. But I should not scoff. I do understand the plight of people who live with tiny dogs whose stomachs are smaller than your average cat’s and who don’t find eating very interesting. One of my lovely friends has a bichon who weighs 5kg. His appetite is poor at the best of times. Tiny morsels of very soft cat food are about the only thing he’ll work for, and only for a short time. Sensitive, small dogs may be more likely to suffer from a full stomach or no real desire to eat. I totally get that. I think we have to use every morsel we can (without putting them under pressure to eat) and keep training to an essentials-only routine.

I can’t say I’ve experienced this one myself, but I’m assured it happens.

#6 You’re asking too much

Many people have shockingly high expectations of what dogs can and will do – particularly for a floury long-life biscuit full of preservatives. They don’t take their time or make it easy enough on the dog. Remember that loose-lead walking and recall can be really tough behaviours to even get right in the simplest of circumstances – walking two metres without pulling, coming back when asked in the garden when there are no distractions. And having done a minimal amount of training, perhaps a couple of days, people then seem to expect their dog to just click. Dogs don’t generalise well, meaning what you do in the home wouldn’t be logical for them to think of doing out of it. The same goes for eating as it does for training. If you only ever ask for a sit and that’s all the behaviour you ever ask for, if you only ask in your home, it shouldn’t be a surprise that your dog doesn’t seem to understand when you ask in the vet surgery.

Make it simple and make it part of your regular routine. Unless you only want the behaviour in a very specific part of your home under very specific conditions, set up a stimulus gradient and help your dog realise that when you ask for a ‘touch’ on a walk, it works the same as when you asked in the car, in the kitchen, in the garden and in Aunt Mabel’s conservatory. When you move to a new place, increase the value of the food again. My dogs may eat the most low quality food simply because I’ve trained them to eat on the go, but if we’re doing hard stuff in new places, the quality of that food increases exponentially.

#7 You don’t have a training relationship with your dog

This is another reason I find guardians may struggle. I’m really proud of the way my dogs can just switch it on, but I do a little training every single day. I ask them for stuff, they do the stuff, I give them food as a reinforcer. They expect this to happen any place, any time. If you don’t invest in training your dog, don’t be surprised when they won’t eat food because they have no idea what your game is. The way we interact is also a reinforce-able, build-able skill. If I want my dogs to interact more with me and take food from me more frequently, well, I need to build that just as I do with every single other thing I teach.

Ultimately though, if you don’t do ninja training – any place, any time – then don’t expect your dog to refuse food.

#8 You serve the food with your hand as a plate

Some dogs do not like hands. Hands are weird. Who the hell made human front legs do what they do? Can you just imagine what that must seem like to a quadruped whose front legs do pretty much what the back ones do? Some hands come with mixed messages. Feeding might be one, but even stroking can be unpleasant for some dogs, depending on how it’s done. Hands may be associated with constraint, with being held against their will, with unpleasant handling and petting. You may see your hands as plates. Your dog may think of them as weird lobster claws. Want to stick your snout near a lobster claw for a block of Dairy Milk? No? Thought not? Also, and I’m not sure how many people factor this in… dogs are mostly long-sighted and the longer your nose, the harder it can be to locate stuff visually that’s close up. If you don’t want to accidentally nip your guardian, hands can be a worry to approach, especially if the guardian doesn’t hold still with the blessed snack.

Also, hands are Dullsville. For dogs who are excited, the biggest game changer outside on walks that I’ve found – the one thing that switches them from ‘not treat oriented’ to ‘snaffle hound’ – is making the food move or making the dog have to find it. Got a scent hound? A beagle? A beautiful bleu de Gascogne? Hide the food and let them use their nose to find it. Take portable snuffle mats out. I promise you that finding a stinky piece of snackage using your great hooter is much more interesting to a scenthound than taking it from a hand.

The same is true for sighthounds and herding dogs – make it move visually! Throw that treat, roll that treat, make the treat have a bit of energy. This is also great for dogs with strong predatory behaviour too. Nothing feels as nice as the grab-bite!

If you’ve got dogs who are heavily into toys and you’d like them to be more interested in food, lotus balls and dummies are great. If you’ve got dogs who are heavily into food and you’d like them to be more interested in toys, lotus balls and dummies are great for that too. Bridge the gap between prey and play, between toys and food, by making the food replicate your dog’s favourite hunting activity.

You also have a little thing called the Matching Law in your favour, as well as the brain’s biology of habit forming. Practise often and you’ll even find that your highly predatory dog (that’d be mine!) will actually stop trying to chase after a deer and will find and eat a dropped treat simply because chasing and consuming a treat is, in some small biological way, like taking down and scoffing a stag. Hunting is not a reliably reinforcing activity. If chasing food is, then you may well find that your insanely high drive, predatory dog actually finds it more reinforcing to chase and eat a snack you’ve tossed across their sight line. And if you use the full weight of habit to help you so that it’s an automatic and instinctive thing to look for and eat a dropped piece of beef, then believe it or not, your dog who isn’t treat oriented because they’re getting all their kicks from the world at large will become a dog who gets reliable kicks from your treat pouch.

#9 You’re expecting Final Boss level and your dog isn’t up to it yet

Life’s challenges can be very much like a video game (See the great book SuperBetter if you don’t believe me). I like to think of our dog’s challenges from that first, early villain they have to defeat on a video game, and their toughest challenge as the Final Boss level. Yet I see so many people dumping their dog in at Final Boss level and the dog just can’t cope (#3 and #6) with low-grade treats in highly demanding situations. If you’ve got a dog who doesn’t like unfamiliar people, then taking them to a café for an hour and expecting them to cope is their Final Boss level. And if you want them to eat, well, they’re still trying to do everything else, not least wonder if they’re safe or not.

In this case, go back down and make sure you’re working at the ‘Goldilocks’ level – not too easy that the dog isn’t learning at all, but not so tough that food is the last thing on their mind.

#10 You’ve wrecked food for your dog

This is where we’ve only used food as a bribe to do bad stuff. The food has come before the bad stuff, and it’s a signal that sets off ‘uh-oh’ alarms for your dog. Like if you only use food when you’re trying to get them to the vet. Or to give nasty pills. If you’ve used food as an incentive or bribe for bad stuff, if you only dig out the biscuits when scary joggers go past, your dog may well see that as a great, big, hairy clue that something bad is about to happen.

So…

If you’re stuck with a dog who you think isn’t treat-oriented, it’s worth thinking of these ten reasons and working out what’s going on. 99% of the time, making it less challenging and adding better food will get you the result you want. However, I do like to make sure I’ve got a dog who’s happy to eat any place, any time. I think it’s essential they’re prepared for my impromptu life skills lessons when and where they occur. I’m also sensitive to their needs. If it’s too hard, I don’t ask. That’s feedback for me to say I need to make it easier. So we do. I’m also conscious there may be things going on beneath the surface if they refuse food where they’d normally take it.

But in sum, if you want a dog who takes food anywhere, you need to build a dog who takes food anywhere, and that is on you, not the dog. It’s very easy for me to be glib about it and tell you to go get better treats, but there are a whole raft of reasons why dogs won’t take treats, many of them interrelated.

With thanks to inspired discussion in the DoGenius Den, especially Rebecca and Nathan.