I’m not going to lie to you. Volunteering can be emotional and it can be messy. Somewhere between the people who come once and make a big song and dance about how magnanimous they are on Facebook, and the volunteers who always, no matter what you ask them, and who say yes time and time again, there are the regular volunteers who are the lifeblood of any charity.

These are the volunteers who come up with new ways to raise money, who offer new ideas. They’re the volunteers who are there on a quiet Friday morning or a lazy Sunday afternoon. They’re the ones sharing on Facebook and helping out behind the scenes. They’re the ones quietly drip-feeding the world around them, keeping the name of your charity in everyone’s minds. Sometimes they’re the volunteers who come in and get their head down and get on with it. Many times, they’re the quiet ones. Often they’re the ones who bring a smile to the world-weary, the ones who turn up and make the impossible into something that’s – well – possible.

In animal rescue, these are the quiet guys who turn up and walk the dogs week-in, week-out. They’re the ladies who you see in the vet’s with a carrier full of sick kittens. They’re the names you see on facebook who run groups and make sure lost pets have the best chance of finding their owner. They’re the faces you see day after day, offering advice to adoptants, doing home visits, helping move animals from one place to another. They’re the people who come up with fundraising ideas and muck in at events, the people with grimy hands who’ve spent an afternoon sorting out assorted bric-a-brac to sell at a car boot sale or yard sale. In between the Armchair Warriors who paste a thousand petitions on their feeds and the weary full-timers, these volunteers are the mainstay of any organisation. And all organisations depend on volunteers like this to keep going.

So why should 2017 be the year to volunteer? What’s holding you back?

Many people think they don’t have enough time to volunteer.

I confess I had a silent tut to myself when I saw someone saying they didn’t have enough time to volunteer because they had ironing to do and a car to clean out.

Some roles take three or four hours, an afternoon maybe. Some people give an afternoon a week. If everybody did three hours a week, charities would be cock-a-hoop. If you have a hundred volunteers who give three hours a week, every week, that’s three hundred hours. That’s only fifteen volunteers per day. Only! But it equates to almost eight members of staff. That three hours a week for a hundred volunteers works out at a budget of almost a quarter of a million euros. Small drops make big oceans.

Some people think they couldn’t handle working with animals. They think they’re not strong enough or that they can’t handle the emotional intensity of animal rescue.

Believe me when I say there are jobs for everyone. You’ll have seen, no doubt, the video of the lady in her nineties who volunteers every day in the UK. We had our own nonagenarian, Louis, who was our “petting therapist”. Every day, he’d sit in reception with a dog who needed cuddles and companionship. Big or small, they hopped up next to him and he spent the afternoon giving some of our dogs the attention they craved. If you can sit, then you can pet.

Other people do other kinds of jobs if they can’t work with animals directly. Some do admin jobs. One volunteer comes in every single time our shelter computers break, which is pretty often. Seeing Florian under the desk is a pretty regular thing. He designs logos for associations as well. Just because you haven’t got time when the shelter is open or you don’t feel able to work directly with animals doesn’t mean there’s not a job for you to do.

Some people feel that language is a barrier – here, in France, if you’re a retiree or a mum who spends most of her time with other ex-pat mums, it can be quite understandable that volunteering can be a bit of a stretch. For that, having bilingual members of staff makes a huge difference. But, where there is a will, there’s a way. I can’t count the number of times our shelter directrice has come up to me and said “I smell a rat!” – I don’t know how much English she ever spoke in her life before so many English speakers descended on her shelter, but I do know that I’ve never seen so many French speakers who aren’t confident with English trying to speak to English speakers who aren’t confident with French. I think that is pretty cool. And, let’s face it, there are jobs that require no interaction at all, if you’re the antisocial type. We have 200 dog bowls that need washing, and 30 cat litter trays to clean out. Grunting is more than adequate. Volunteering in France will definitely help your language skills. Believe me. When you’re trying to explain the consistency and colour of diarrhea, you’ll find your language expanding miraculously. And there is always someone to help you.

It’s not all about what’s in it for the shelter, though.

What’s in it for you?

Volunteering in France is a great way to learn the language and to become truly part of something. It was through volunteering that I actually – after five years of living in France! – found actual, real-life French friends. Not clients or people I work with. Not mums from school. Actual friends who invite me to their houses sometimes. If you live in the Charente, you’ll know that this kind of stuff usually doesn’t happen unless you have known someone for fifty years or you accidentally married a French person.

You learn a language and make friends because, guess what, volunteering is great for building a sense of community. Doing good things makes you feel good too. It reduces depression and it gives you a purpose. The routine is vital for those who are suffering with depression, and feeling part of a community is a big part of great mental health. It brings you in contact with people you would never have met in any other way and it forges friendships that would never have happened in a world beyond volunteering.

When you volunteer, you meet people. If you’re like me and you work too, that puts you in touch with a whole new business market. Don’t get me wrong, I’m tired of the cynical sellers connected to the pet industry who want to use the shelter as part of their plan to branch out to new customers. Be they pet food sellers, dog trainers, photographers or kennels, there are definitely some pet industry professionals who are in it for clients. But there are plenty who are pet industry professionals because they love pets, and more clients are accidental by-products of volunteering. If you come at it from the angle of “this will expand my target audience”, you’ll fail miserably. If you come at from “I love animals!” that will stand out a mile. And you might be at odds for how this will help you if you’re in an unusual business. I can’t count the number of times I’ve pushed my crafty friends in the direction of one of our volunteers who also runs a craft business. Personal connection is everything for word of mouth, and volunteering gets you out of your usual circle of contacts. You just don’t know what other volunteers get up to in their day jobs, but you can bet your bottom dollar that once they find out what you do, they’ll be happy to recommend your services.

Volunteering is also a way to improve your confidence, especially if you’re more wallflower than party animal. Most of the volunteers at our shelter are fairly extroverted, but there are plenty who are shy guys or prefer to just get on with it. It’s great for reminding you what you can achieve, especially if you’re feeling unsure of yourself.

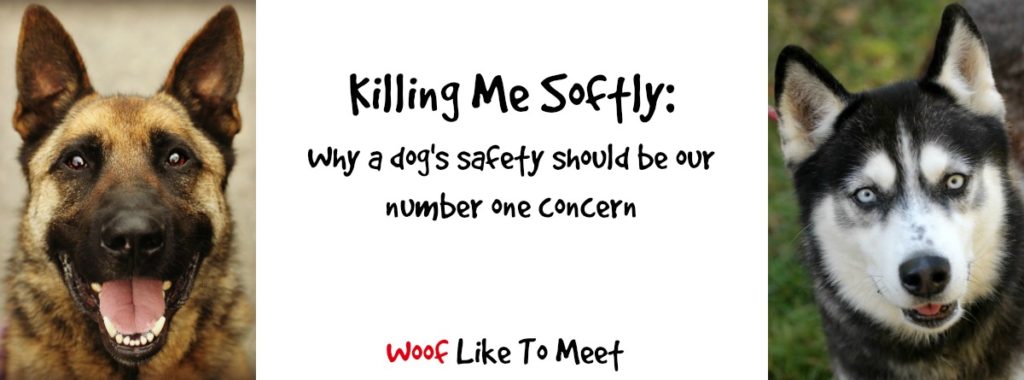

It can also help you learn new skills, or apply your skills in ways you never did before. Take me. I’d studied photography, but had never really done much between landscapes and travel photography. Now I have 30000 photos of dogs and kittens on my laptop. I’ve had to use Photoshop and editing programs like Inkscape in ways that I never had before. It also got me interested in how animals learn. I’ve got a masters in how people learn and I loved psychology at university, but now I am loving having this mid-life turn of focus. I still love teaching English Literature. It will always give me a thrill to get teenagers to the point where poetry isn’t horrible anymore. And I still love writing. In fact, it’s given me something to write about! But volunteering is also the reason I’m studying further, and almost half way through a canine behaviour and psychology course. I’m really, really looking forward to writing my dissertation and blending all that I know about changing people’s mindsets with working with animals. So many dog behaviourists say that the owners are the problem not the dogs that I’m looking forward to exploring the shadow side of working with human clients over dog problems. Volunteering has invigorated me and given me an opportunity to bring what I know to a different arena. That’s pretty exciting. My book list is enormous, and it’s all about animals – so much so that I have turned into a colossal bore, I’m sure. I was talking about altruism in birds at lunch yesterday. I’m sorry to the people I was with. Luckily, they tolerated my enthusiasm and we ended up talking about sweary parrots on Youtube.

Volunteering also allows you to give back to a cause that you believe in. For so many years, when I worked full time, my donations were financial. Now I’m really enjoying the practical side of volunteering and a chance to do something a little different. It also turns you into an advocate. How many of us have been convinced to adopt a shelter animal by someone who worked with or believed in second chances for animals? That’s pretty powerful.

It can be fun too. I mean belly laugh kind of fun. You’d probably not think that working in animal rescue could be fun. A few weeks ago, a member of staff enlisted me for a pick up in a dodgy part of town. We had a nervous Amstaff and a Malinois who hated the Amstaff to pick up. And a cat. It was pretty horrendous, and it was pretty sad. The poor Amstaff wouldn’t get in a crate at all, so we had to drive kind of holding her over the seats, and the Mali was so distressed that she did a massive poo in the transport crate. When we got back, there was shit everywhere. I mean everywhere. And you can’t leave that shit for someone else to clean up. Nope. That is YOUR job. Well, the unfortunate member of staff hadn’t got the hose pressure just right and ended up getting a back spray of dog shit. I cried laughing. It just couldn’t have been any more shitty than it already was. We both ended up crying laughing, and it was absolutely the best medicine. If you don’t have people to help you find the ridiculous in amongst all the shit, helping work is pretty flipping miserable. In the rain, in the mud, the sight of two volunteers wearing bin bag skirts and silly hats just turned the whole sad misery of life in an animal shelter on its head. Now I know that dogs appreciate laughter more than tears or anger, and our laughter is vital to the animals’ mental health. That’s what I tell myself. I can even show you studies about tone of voice and what’s going on in a dog’s brain when we smile. Smiling volunteers are essential for sad dogs. Fun and laughter is good for our souls as well as for theirs.

And if, just if, you find a dog or a cat that you fall in love with? Well, who’d argue with that?

So go on, I dare you. Make 2017 the year you volunteer. Stick it on your New Year’s resolutions list. Sign up today. Don’t put it off a moment longer. We need you! Dig out your Yellow Pages and find somewhere – anywhere – that needs a helping hand. I guarantee you’ll start 2018 feeling really glad that you did.